Without Sanctuary

Lynching photography in America

By Walter Howerton Jr.

Are we that foolish? To believe a thin tissue of promises – especially the smug and purse-lipped promises that cover our darkest deeds – will protect us from who we are or who we have been? Of course we are. We are human, and sometimes that is a terrible thing to be.

Lynching is just such a secret.

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America is a new book from Twin Palms Publishers of Santa Fe. The 95 photographs all come from the collection of James Allen, an antique dealer in Atlanta. Some of the lynchings are from the 19th century, but most belong to the early decades of the 20th century, our own century just passing, when lynching was at its horrifying peak.

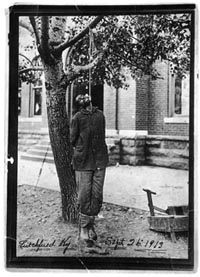

The photographs are brutal. They are not art. Rather they are part of the act of lynching itself, snapshots, photographs bearing the names of proud professional studios, mass-produced postcards cheerfully sent home. They are documents born in the artless thuggery of history. Our history. American history.

They come from all over the U.S. map. There are hangings, burnings, cuttings and shootings in California, Montana, Nebraska, Illinois, Indiana, New Mexico, Minnesota, Ohio, and from places all over the South.

The victims are not always black, but whether it is three black men hanging from a lamppost in Duluth, Minnesota, Laura Nelson a black woman hanging from a steel bridge in Oklahoma alongside her 14-year-old son, or the charred corpse of a black man dangling somewhere in Georgia or Tennessee or Mississippi, they usually are.

The lynchings of black people – particularly black men – run through Without Sanctuary like a thick and damning theme straight out of William Faulkner and stain the map of American history. No distant geography or home ground in their own country could save these people from their fellow citizens. Their usually unpunished tormentors were fueled by self-righteous moral indignation, a mob-inspired self-justifying rage, the hunger for spectacle in lieu of justice, race hatred, or, worst of all, the plain white habit of torturing and killing black people.

Kentucky

is not spared.

Joseph Richardson hangs from a tree in Leitchfield, one shoe on, laced tight, the other on the ground beneath the bare dead toes of his left foot. A mob snatched him out of jail believing he had assaulted a little girl. The photographs were hawked door-to-door, where the victim was recognized as the town drunk, a man someone said later had “merely stumbled into the child, and not even torn her dress.”

Ernest Harrison, Sam Reed and Frank Howard hang side by side from a rafter in a sawmill, the teeth of a saw blade visible in one corner of the picture. The sawmill is in Wickliffe. These lynchings attest to the univerality of the impulse to seek the instant gratification of revenge rather than trust the slow machinery of justice. The three confessed murderers of a respected black man reportedly were lynched by a mob of blacks.

The corpse of Leonard Woods sprawls amid a circle of white men in Pound Gap. They shot him more than 100 times then set him ablaze for killing a mine foreman. The mob wanted to lynch two black women they found in the Whitesburg jail with Wood, but he saved them by convincing the mob they had nothing to do with the shooting.

Virgil Jones, Robert Jones, Thomas Jones and Joseph Riley all hang dead from a single tree in Russellville in Logan County. Their crimes are unknown but the postcard of the hanging was circulated with the message, “Four niggers hanged by a mob in the State of Georgia for assaulting a white woman.” A message is a message, no matter if the dead men and their tree were several states away from Georgia and there is no mention of any actual crime they committed.

The tree in the photograph has its own fame. A note in the text from the time of the hanging in 1908, claims that with the deaths of these four men, at least nine people had died on the branches of the “Old Proctor Lynching Tree.”

Five plus four. That is nine. Only nine? But who’s counting? It is impossble to look at this book without understanding one thing: Black life was rendered so cheap that it must have seemed to other Americans that all of the killing never would add up to very much. White people count; black people don’t.

There is a forest of lynching trees out there.

The numbers themselves are frightening evidence of how common lynching was.

Scholar Leon F. Litwack, whose essay is one of three in the book, writes that an estimated 4,742 blacks were lynched in the U.S. between 1882 and 1968, though it is believed the number really was much higher. At least that many more died in “legal lynchings (speedy trial and execution), private white violence, and ‘nigger hunts'” in a country determined to control its black citizens, according to Litwack.

Lynching sent a message. Most of these photographs were meant to make sure the message was clear. Some were mass produced -one photographer recalled printing photographs day and night for days because demand was so high – others made into postcards, some of them hand tinted, for the widest possible distribution.

The new book’s publisher Jack Woody believes they still are sending a message, but not the intended one. “They are about our history, who we are. We claim [as Americans] that we always held ourselves to a higher standard. These were not in my history books when I was a kid. They raise questions about what we teach about our own history,” he said. “History is passed on this way. In books.”

The book is beautiful, but its beauty offers no sanctuary because neither history nor aesthetics can create a comfortable distance from such terrible things.

And it is not just the victims, their necks stretched and broken, their flesh torn and scorched. The dead insist on being looked at and our own nature insists we give them their due. If the book were only about the dead, it would be easier to look at somehow, once-upon-a-time easy, dead-old-history easy, but it’s not. History exists where memory once was, but these pictures conjure something too much like a memory, something secreted away that refuses keep still or become history.

“First you see the victims,” Woody said of the photographs. “Then your eye drifts down to the faces in the crowd.”

The

Crowd

In one way or another, lynchings had to be public acts. Otherwise they would have been pointless. Sometimes they were the act of a small band of determined citizens; sometimes there were unruly mobs; sometimes they were announced in advance and drew huge crowds including school children on holiday for the event.

In one of the most striking images in the book, several young white girls who seem to have dressed up for the occasion, stand at the base of a tree looking up at a dead black man. There is no real horror on their faces, though one of them innocently and gracefully crosses her wrists in front of her almost as the dead man’s wrists are bound grotesquely in front of him.

In others, men with white faces crowd into the frame, eager to be photographed with their victim, eager for the world to know what they have done. Sometimes they are faces lost in the crowd, pointed out for the folks back home on a postcard with an arrow. Sometimes they pose with their victims. Often they smile.

In his foreword to the book, Georgia Congressman John Lewis writes: “What is it in the human psyche that would drive a person to commit such acts of violence against their fellow citizens?”

There is no answer to be found here. The victims and the crowds – citizens all – simply inhabit the grim world of these photographs. It is here, somewhere in the intimate interaction between the living and the dead that we must see ourselves and come to terms with the high price exacted on us all, one death at a time.

It is strong stuff, but people are not turning away.

In addition to the book, 60 photographs from Allen’s collection have been on display at the Roth Horowitz Gallery in New York City for the past month. The gallery is small – about 25-feet by 25-feet – and only a few people at a time have been able to go inside, but there were long lines outside the show for four weeks. Oprah Winfrey went to see it. The New York Times has written about it twice. The show was mentioned in The New Yorker, which also ran one of the photographs. The Los Angeles Times printed a column about the show and the book on the front page and a lengthy review in its books section. Patricia K. Williams wrote a column about it in The Nation. The Today Show spent 10 minutes on it. Foreign television cameras visited the gallery. Public television devoted a segment to the book and the show.

The first printing of 4,000 books sold out; a second printing of 6,000 has been ordered and already is on the way to being sold out. A third printing is planned. The gallery show will move to the New York Historical Society in March. A traveling exhibit is in the works.

Twin Palms publisher Woody is surprised by the huge response to the book and the show. “There is no way to plan for something like this,” he said.

People warned him it would be “messy,” even dangerous to publish a book on lynching. Some people called and asked to be dropped from Woody’s mailing list when they found out about it. “Some people said it would be inappropriate to have photographs like these in an elegant book or a museum show,” Woody said. The International Center for Photography in New York City would not touch the show, even though Woody had worked with them extensively in the past, a decision Woody said ICP already regrets. That is how it ended up at Woody’s friend Andrew Roth’s little gallery.

Woody has been publishing books for 20 years. “One thing I said I would do is publish books other people wouldn’t do,” he said.

Woody said he had been interested in lynching photographs for years. He said he is fascinated by the “kinds of itches” that lead people to document such things. He had run across them at flea markets and antique shows, but that he knew very little of their history. “I knew what they were on the surface,” he said. Doing a book would give him a way to learn something, but he couldn’t find enough images for a book. Then he heard about Allen, who had a collection of 200 images on permanent loan to Emory University in Atlanta. He said he and Allen shared a view that the photographs belonged to history, not to collectors.

“The press always is a reflection of my personal interest at the time,” Woody said. “It is my life at this point.” He went ahead with publishing Without Sanctuary, not sure what to expect.

“But the response has gone in the other direction,” he said. “This is my fastest selling book in 20 years. There have been lines around the block at the gallery. There is a great demand to see these images. I am not sure why.”

Whatever the reason, the secret is out. People are looking into the darkness and, perhaps, catching a frightening glimpse of themselves.

“The photographs provoke a strong sense of denial in me,” Allen, a white southerner, writes of his own collection. “Then these portraits, torn from other family albums, become the portraits of my own family and of myself.”

“Lynching is not a relic of the ancient past,” Williams, a black attorney, wrote,”but a piece of our modernity. Its repercussions shape not just blacks but millions of white people who are very much alive.” [Her column is reprinted in CityBeat.]

Black writer Hilton Als also contributed an essay to the book. It is not an easy task for him to write about the photographs, hard to be house boy to “white editors…hiring a colored person to describe a nigger’s life.” The message of the photographs is obvious enough to him. And it is a message with presence, not absence.

Als recalls going to see Gone With the Wind as a child, being caught up in his love for the suffering Scarlett O’Hara, wanting a woman just like that and only later understanding:

“For sure, Scarlett, in real life, might have lynched a nigger in order to make that person pay for all the inexplicable pain she had gone through and eventually came out the other side of, a much better person. After that, her world might have looked completely different.”

All of us, black and white, know what he was talking about. It is the secret memory that refuses to be history, the knowledge that haunts us and haunts us and haunts us. After all, it was not that long ago that a black man was dragged first to death and then to pieces on a dark Texas highway.

Let those who would know, look and pass it on to their children. Let those who would rather hide from the truth buy their sofa-sized mass produced art at Wal-Mart. Nostalgia comes cheap. The truth always exacts full price. It never is discounted.

###

Lynchings in Lexington

By Tasha Taylor

Many Kentuckians are proud to point out that we were a neutral state in the Civil War. Technically, the state did not fight for or against states’ rights, secession, or slavery. Knowing the human rights atrocities of this era, this neutral frame of mind both soothes the soul and eases the conscience.

But lynching in Lexington continued long past the Civil War era – both the legal and mob-sponsored variety.

“Lynching was as popular as baseball. That’s what was so horrendous about it. This was simply a pastime for many Americans.”

Chester Grundy, Director of the Office of African-American Affairs at UK states that throughout history lynchings were “carnival like” events. “Hundreds and sometimes thousands of people would come to watch a lynching. They dismissed schools for the event. Mutilation occurred such as cutting off the accused’s fingers and passing them out into the crowd. People took pictures posing next to the swinging body like they were at a carnival. Lynching was as popular as baseball. That’s what was so horrendous about it. This was simply a pastime for many Americans.”

According to Racial Violence in Kentucky, 1865-1940, by George C. Wright the history of the city of Lexington is filled with acts of racial violence and hatred not long ago. Many great-grandparents and grandparents would remember.

“It was more part of American culture, a ritualized practice. This was common and accepted, especially in the South. Lynching was not always punishment for a crime. It was a way to keep the black population complacent,” says Grundy.

No one knows for sure how many lynchings occurred in Kentucky’s history. Wright suggests that his research of Kentucky newspaper archives indicates 353 people were lynched in Kentucky. Other researchers have estimated the count at 205.

What are the stories behind the lynchings? Both the victim of the crime and the nature of the crime contributed to the possibility of a resolution in lynching.

One story told by Wright recounts that one death was not always appeasement enough. In early 1878, a black man from Lexington named Stiver killed a white man and was lynched. This one lynching did not provide sufficient “justice.” A white mob confronted three other black men who were thought to have aided in the first murder. The first black man found was shot at his home in front of his wife. The other two were found and hanged in woods in a surrounding community of Lexington. An eye for an eye, and four black deaths for one white death.

Lexington then joined Louisville in making executions private and charging admission. There is no mention of what the city did with the profits from this elite spectacle. According to Wright, “Thousands of Louisvillians and Lexingtonians of all ages paid for choice positions where they could look over walls or from rooftops and observe the private hangings.”

In the 1920s, Lexington went through the motions legally to end mob violence. Democratic governor William J. Fields took over the murder trial of a Lexington black man accused of killing Clarence Bryant and his two children and the rape of Mrs. Bryant. During the trial, the city was under a state of martial law, closing down all roads in and out of Lexington. The black defendant was put to death anyway. His trial lasted sixteen minutes before a decision was made.

It is not surprising then that the number of legal executions grew in both Jefferson County and Fayette County. Thirty percent of the state’s legal executions occurred in these two counties. In fact, whites in urban areas prided themselves on preventing lynching. Small communities often sent their convicts to urban areas like Lexington and Louisville for protection from lynching violence. The justice system dealt with the deaths almost as quickly as the mobs had. Now it was labeled “legal” and “just.” The last of these legal executions occurred in Mercer County in 1939. The defendant was a black man charged with rape.

“You could regard this as America’s holocaust. Lynching, as well as other acts of violence, really can be considered a holocaust,” says Grundy.

The Publisher

Jack Woody has been in the publishing business for 20 years. His Twin Palms Publishing and Twelve Trees Press are located in Santa Fe.

“One thing I said I would do is publish books other people wouldn’t do,” he said. And he has been as good as his word.

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America is only the latest in a number of controversial books. The Killing Fields, a book of pictures of the faces of victims of Cambodia’s Pol Pot also drew criticism — and a major museum show in New York. He also has published the troubling and controversial work of Joel Peter Witkin. He has published gang photographs by Bruce Davidson and the gritty work of Danny Lyon.

He is interested in what he calls the “kinds of itches that come out of documentary photography” and also published A Morning’s Work by Dr. Stanley Burns, a book of medical photographs taken from 1843 to 1939.

He also published the first work of glamour photographer Herb Ritts and others, work he said he “probably would not publish now,” but calls historically important.

Famed photographer Duane Michaels, who Woody describes as “sort of like a surrogate father,” has had several books published by Woody.

The press is at www.twinpalms.com. -WHH