“Have you heard about Wayne, he deals the cocaine a little more everyday…”

–the Clash, from “Jail Guitar Doors”

[one_half]

Funnyordie impresario Adam McKay will have another movie on screens long before Anchorman 2 hits theaters, and it will air on public television.

Legendary MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer will be profiled on the PBS Lifecasters series in February 2013, in a segment from (Anchorman and funnyordie.com filmmaker) Adam McKay and McKay’s wife Shira Piven.The short film, The Beast and the Angel, chronicles the punk pioneer’s activist life.

Kramer (along with Billy Bragg) is a co-founder of Jail Guitar Doors USA, the self-proclaimed “loudest charity on planet earth,” a music non-profit that provides instruments and opportunities to help rehabilitate inmates.

Kramer’s friends McKay and Piven are board members of Jail Guitar Doors USA. McKay is the founder of protesttunes.com, and an outspoken advocate of justice reform.

Lifecasters executive producer Gita Pullapilly writes:

“Margaret and Wayne wanted Adam McKay and Shira Piven to tell their story and we knew that they would be able to create a very intimate and personal profile on Wayne given the already established trust that existed between the filmmakers and the film subjects.”

Kramer narrated the 2008 documentary aired on PBS, The Narcotic Farm, based on the book of the same name:

“From its opening in 1935, the United States Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, epitomized this country’s ambivalence about how to treat addiction. On the one hand, it was a humane hospital set on 1,000 acres of farmland where drug addicts could recover from their habits. On the other hand, it was an imposing federal prison built to incarcerate convicted addicts.”

Jail Guitar Doors USA: the Mission

from their site: “Jail Guitar Doors USA seeks a more fair and just America. We are a 501(c)3 non-profit organization based in Los Angeles, California providing musical instruments and opportunities to help rehabilitate prisoners. We organize prison outreach programs and produce concert events. We advance new solutions to diminish prison violence. We support organizations that engage in policy reform efforts and partner with social service groups to help people in prison reconnect with the outside world.”

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

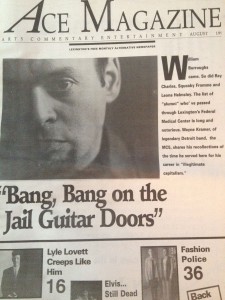

Bang, Bang on the Jail Guitar Doors:

An interview with Wayne Kramer

…an excerpt from the Ace 1995 archives

BY STEVE POULTON, August 1995

…Wayne Kramer of the MC5 served two years here in the mid-70s for what he describes as his career in “illegitimate capitalism.” He generously shared with us his recollections of his time at the Federal Correctional Institution in Lexington.

He is the former guitarist for the now legendary and highly influential Detroit group, the MC5, whose music combined elements of free-jazz improvisation (a la Archie Shepp, John Coltrane, and Sun Ra, etc) with more traditional and comparatively simple rock-song structures, played at planet-splitting volume. (I play the guitar and the amp,” says Wayne.)

The breakup of “the Five” came after just three records, amidst drug related problems within the band. Wayne was reduced to hustling dope on the streets of Detroit to keep the wolf from the door. And he was using, too.

“Crime is really exciting stuff,” he says. “After the breakup [of the MC5], I was no longer a star, so to speak, in the world of music. I saw all these other bands like Ted Nugent and KISS become huge. Fuck, my band was so much better than someone like KISS. But there are stars in the drug world too. It was just an easy option.”

Wayne’s career in “illegitimate capitalism,” as he calls it, was even more brief than that of the MC5. Arrested in 1974, Kramer was charged with distribution of cocaine and received a four-year sentence, the last twenty-six months of which he served at the Lexington Federal Correctional Institution. So what was jail like — a day in the life?

Brother Wayne kicks it to us thusly:

“[Lexington] had a reputation as a good place to do time. It was pretty much to the left of the spectrum as far as institutions go. There was more of a focus on rehabilitation than atonement for your crimes. I had a lot of time to think.

“Everybody had to work, if you could work. Some people made furniture, whatever. My job was doing the layout for the prison newspaper they had in there, ’cause I had some artistic ability. I could draw. I did some cartoons and stuff. I got paid $20 a month. That was considered a good job.

“I went to bed around ten. I had a transistor radio and I listened to this college station [WUKY] that played jazz. It would go off the air at like eleven and come back on at seven in the morning and that’s when I would wake up. It was pretty cool actually. I worked five days a week, got off at four in the afternoon. They had ‘count time,’ five times a day. They counted you after lunch, before dinner, again at seven, ten-thirty, and three in the morning. I ran in the yard every night. Seven laps around was a mile, and at the end I was doing like five miles.

“I shared a cell when I first got there. The rooms were like hospital rooms — big heavy doors with a little window. There were bathrooms on every hall and kind of like a lounge, called the ‘day room,’ where we had all kinds of group [counseling], RBT, which was ‘rational behavior training,’ PMA, which was ‘postitive mental attitude,’ ‘transactional analysis,’ and what we called our ‘alley group.’ That was a twelve-step program, kind of like Narcotics Anonymous. That was just for our hallway, but it wasn’t very organized.”

Kramer was released from FCI in the spring of ’78… For the final three months of his sentence, however, Kramer was able to work outside the FCI counseling kids at the Fayette County Juvenile Detention Center.

“It was pretty cool; I got to leave [the grounds of the FCI]; eat lunch downtown. Most of the kids had already fucked up pretty bad. It was sad, but I could talk to them ’cause I had been there. Maybe I helped a couple of ‘em. A lot of them were paint huffers though. I had never even heard of that. Yeah, jail saved me. It’s not a sore spot anymore. I got out and I’ve been clean since the mid 80s.”

Wayne assured me that these days, he’s “living right.” After years of earning his living as a carpenter in the Florida Keys and Nashville, Wayne has relocated to Los Angeles, is happily married, and is once again, dare I say it, kicking out the jams.

Click to read the Ace 1995 cover story archive.

[/one_half_last]