Guy Davenport was a lodestone for the intellectual life that converged in Lexington in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

Drawn in by this Georgia-born, Harvard-educated “one of the last true Modernists” were friends and colleagues that included Wendell Berry, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Ed McClanahan and others. Davenport’s essays, poems, translations, paintings and fiction drew the respect and interest of these contemporaries and of students who would shine their own lights widely.

One of the last drawn to Davenport’s side by the sheer power of his intellect was Erik Reece, the author of “Lost Mountain” and several other books. Reece, one of the last to study with Davenport at the University of Kentucky, where he was a professor in the Department of English, was appointed as Davenport’s literary executor . He is the editor of “The Guy Davenport Reader,” just published on Counterpoint of Berkeley.

On Sunday night, Erik Reece was scheduled to give a reading from the book at Morris Bookshop in Chevy Chase. And that is a great event — Erik Reece reading.

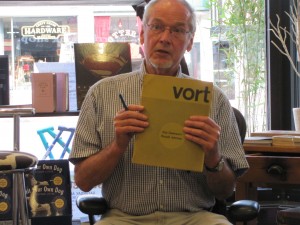

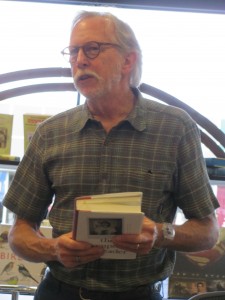

But Reece tossed the mic immediately to the great photographer Guy Mendes, who talked about taking classes with Davenport and Meatyard before reading a passage of the “Ralph Eugene Meatyard” essay by Davenport in Reece’s reader. It was difficult to see where the selvage ran on this fabric enfolded with three generations of Kentucky cultural icons.

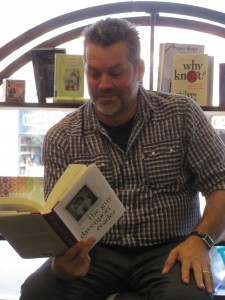

Erik Reece, one of Davenport’s most beloved proteges, took his place after Taylor, speaking quickly and familiarly about Davenport, providing context on a translation of a fragment, a work of fiction, the classic “On Reading” and finally on his own afterword to the collection — reading each with the perfect conveyance for each different form. He took the audience, with finely brushstroked description, with him as a 20-year-old on the mile walk from the grocery with his teacher, collecting firewood, into the very study with the “two worn chairs” at the fireplace, where somehow, he said “Guy Davenport taught me to think and to write,” his brilliant blue eyes glistening with tears that seeped into a graying beard.

And then Erik Reece told the group that he will be teaching a course on “Kentucky’s Literary Legacy,” the one forged by Guy Davenport and all the satellites drawn and excited by his magnetism, this semester at the University of Kentucky.