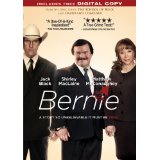

Richard Linklater’s Bernie was released in theatres this spring and on DVD earlier this fall, with little fanfare other than that reserved for Jack Black’s eponymous performance, now nominated for a Golden Globe.

There are no spoilers for anyone who’s seen the trailer or an ad. The movie is the story of Tiede, a Carthage, Texas assistant funeral director who confessed to killing the mean, rich widow Marjorie Nugent (played by Shirley MacLaine), whom he’d served as a sort of companion/confidante. It isn’t a whodunit story, or even a why. It’s really just a prolonged character study.

The two meet and bond, after a fashion, over the funeral of her oilman husband. He extends her the kindness and consideration he might show to any grieving widow. She has no friends, and is estranged from her family. “It was easy for her to disappear…no one was looking for her.”

Linklater has staged the movie with some actors and some real-life Carthage citizens providing narration and Greek chorus-style commentary. Consequently, MacLaine doesn’t get to show off the ugliness of Marjorie’s soul so much as she plays out a few hateful episodes, and the rest is narrated for her. Because she’s afforded so little onscreen development, her performance comes perilously close to becoming a caricature of her most legendary eccentric Texas widow, Aurora Greenway (“why should I… why should I be happy about being a grandmother?!” “Give my daughter the shot!”) She does bark orders and emasculate Bernie every chance she gets, and she chews every bite of food 25 times, but there’s nothing onscreen to earn her four shots in the back, and a stay in the deep-freeze.

Poor Matthew McConaughey (a revelation earlier this year in Killer Joe) barely gets to chew any scenery at all as D.A. Danny Buck Davidson, “we might be dealing with a mad man here…a bona fide De-Ranged killer.” (He arguably owes Linklater his career, thanks to his 1993 Dazed and Confused debut, so the favor here seems slight — the least he can do, really, and that’s exactly what he turns in.)

One observer tells the camera, if Marjorie was displeased,”she’d rip you a new three-bedroom, two-bathroom doublewide asshole.” Her sister tells the camera, “she’s my sister and I guess I should love her, but she’s mean.” The mockumentary sequences are colorful, but they also distract from the relationship forming onscreen between Marjorie and Bernie, and impede any natural momentum the story might gather.

None of this — the slightness of detail, the structural problems — take anything away from Black’s performance, which is a delight. He plays Bernie straight (as it were), as the town’s Robin Hood “bachelor” who’s described as everything from “light in the loafers” to “somewhat of a sissy.” He is beloved, and does far more good with the Nugent fortune than Marjorie ever would. But part of the townspeople’s initial disbelief that he shot Marjorie comes from their dubiousness that he’s “man enough” to handle a gun. He never pauses to nudge or wink at the audience. He is all in, belting out show tunes and gospel hymns, and sweetly charming the pants off all comers. Accustomed to the first class life Marjorie’s companionship affords him, his exasperated eye-roll as he takes a call from her while climbing down from his small plane, is genuine. “This is my life,” he sighs, without a trace of irony.

Will he be able to take out Hugh Jackman in Les Miserables on Golden Globes night (or “Less Miserables” as McConaughey pronounces it in a courtroom scene mocking Bernie’s Ritz Carlton tastes)? Or an even sterner Oscar field? Not likely. (An Independent Spirit award? Almost definitely.) In this case, it probably is an honor just to be nominated. But Philip Seymour Hoffman has built a heavyweight award-winning career on roles such as this, and Black could be destined for a comparable arc.