It would be difficult for today’s digital natives to imagine just how influential a thumbs up or thumbs down from Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel could be on their first show, Sneak Previews on PBS, and later their syndicated At the Movies. There wasn’t much of a set, and there were no real production values or fancy graphics. It was just two critics in a couple of theatre seats who loved the movies and (at times) hated each other, providing a vigorous debate on the week’s releases. They both loved M*A*S*H and Nashville and Last Tango in Paris and the Exorcist and Mean Streets and The Deer Hunter and Breaking Away and My Dinner With Andre. They differed on Armageddon and Home Alone 3 and Starship Troopers and The Cable Guy. They both hated Weekend at Bernie’s.

Ebert wrote in 2012, “If you handed me an iPhone and a Netflix or Hulu Plus subscription in 1974 — I would have thought I had died and gone to heaven! (Especially if you grew up in the rural South, and you knew that you would be forever denied any chance at all of seeing a movie by this guy Bunuel that Pauline Kael raved about unless you moved to a big city.)”

Populist as she sometimes was, Pauline Kael might have left a more scholarly intellectual imprint, but no 1970s movie lover is likely to forget an impassioned, “I hated, hated, hated this movie!” from Ebert.

Forty years later, everyone’s a critic. Literally. With the advent of blogs and social media, your opinion can be instantly transmitted to (potentially) millions. The movies themselves are at our fingertips — tickets can be summoned on an iPhone that wasn’t even a glimmer in Steve Jobs’s eye when the two of them got their television start in the 70s. Everyone may have an opinion, but even if the internet has democratized criticism, some opinions are still more equal than others, as Ebert abundantly proved when he carved out a considerable niche for himself with RogerEbert.com. Though the site in its current incarnation is no longer the tastemaker it was when his voice drove it, it is no small miracle of technology that decades and decades of his reviews are archived there. Wanna know what he thought about Deliverance in 1972, here it is. How about Ice Castles? It’s here too. Prolific as he was, the volume is so staggering that it’s easy to miss the small, elegant moments, like when he wrote in his 2012 review of Seeking a Friend for the End of the World, “That’s when I realized what I would do if I knew the world was ending. I would find a homeless mother dog with puppies and be calmed by her optimism.” He had less than a year to live when he wrote that review. Every review we’ve ever published, including the one for little indies like that one, owes a debt to the memory of him and Siskel closing out the weekend’s programming on a wide black and white screen encased in a wood veneer box, with their cheery reminder to “save us the aisle seat.”

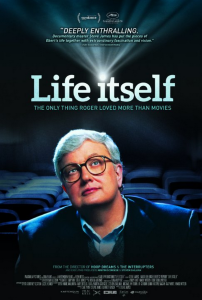

Fellow Chicago native son, Steve James, was the right choice to make the documentary of Roger Ebert’s life, Life Itself. Drawing heavily from Ebert’s (not that great) 2011 memoir of the same name, James (Hoop Dreams) paints a non-sentimental portrait of the large-living cantankerous lifelong journalist and film critic that could’ve easily devolved into an E! True Hollywood Story, but never does.

It becomes sadly and immediately apparent that this won’t be the movie either of them set out to make. After developing a hairline fracture in his hip, Ebert detours to yet another stint in a rehabilitation facility. Most of the present-day footage is of his brutally physical struggles — invasive, intrusive, and distressing as they are to watch (his g-tube feedings, the nurses suctioning what’s left of his throat, his struggle to walk), the camera doesn’t flinch.

The film unsparingly chronicles the news that his cancer has metastisized again, and he accepts the information, typing into his MacBook the recognition that it’s likely he “will have passed [by the time] the film is ready.”

He says, “I have no fear of death. We all die.” His wife Chaz has a harder time finding her footing in the wake of the bad news. She admits that there was once a point in his health struggles that he wrote a note that said, “Kill me.” But there’s no evidence of despair in how he’s chronicled in the documentary. He remains realistic but optimistic, and full of plans for online expansion and world domination. Ebert died in April 2013 after years of battling the cancer and unsuccessful surgeries that failed to restore his voice or ability to eat or drink, leaving him disfigured, with his jaw missing. His death came within days of the 46th anniversary of his Chicago Sun Times columns, and his “leave of presence” column was filled with plans for the future.

It was 2002 when Ebert had his cancerous thyroid removed and appeared to recover quickly. In 2006, cancer returned, and he lost his lower jaw, and nearly his life. A popular Esquire article in 2010 chronicled the battle. In 2008, having lost his physical voice, he found a new one online, blogging about everything from Does God Exist? to Watching Movies on Cellphones. Ahead of the curve in a way that most old newspaper men were not, he quickly embraced social media, and found a devout Twitter following anxious to keep up with his thoughts on current movie releases, along with musings about politics and pop culture. He saw the digital revolution not as competition, but as a renaissance, a revival of the public square nature of journalism. He would’ve surely appreciated the fact that the making of the documentary raised $153,000 on indiegogo.

The best parts of Life Itself (the movie) are the outtakes from his days with his fellow movie critic and sparring partner, Gene Siskel.

Ebert lived a long, colorful life. He is no saint and the documentary never makes him out to be one. His friends recall his hard-drinking days before AA (where he met wife Chaz, which she divulges for the first time here), and his exchanges with Siskel are often brutal, and sometimes hilarious. (As mean spirited as their rivalry could often be, their joking in between takes is welcome comic relief, “Protestants: people who sort of want a religion,” Ebert laughs, cracking the two of them up.) Although the two evolve to a grudging brotherly love for each other over a professional lifetime spent together, Siskel’s widow is candid about some episodes of Ebert’s petty smallness (she says he once snagged a New York cab out from under her when she was eight months pregnant.)

Ebert’s final days are not spent on camera, and he is ultimately unable to complete James’s nine pages of questions that would have doubtless filled in some entertaining blanks. He is sent out with a wake that (much like his wedding) would rival that of heads of state, and it’s a wake that continues in the online community of movie lovers that he built.

Life Itself, in limited release now, is also available on Video On Demand and itunes.