The great movies so often want to wallop us with the passage of time. Some filmmakers try to do so through grand compressions – think of Stanley Kubrick fitting the history of civilization into his famous smash cut between a bone sailing through the sky and a spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Others dazzle us by going out of their way to avoid the distortion of time. Think of the extended takes in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas or Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, which stage grand choreography without breaking the flow of time – they’re trying to remove the lie that’s in every cut, to paraphrase Jean-Luc Godard.

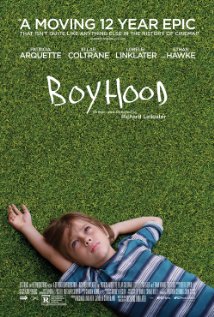

Richard Linklater’s Boyhood is at once an impressive compression and an even more impressive removal of a standard cinematic lie. The compression comes from the film’s attempt to capture almost the entire life of a boy in Texas named Mason (Ellar Coltrane) within a running time under three hours. The lie-removal is in Linklater’s much-discussed method. The inevitable stunt that most filmmakers have to resort to in telling a coming-of-age story is to select a narrow age window to focus on, or use different actors to play different ages. Linklater instead shot the film a few days at a time over 12 years in order to capture the actual physical growth of his star over time, as well as the aging of the actors playing his mother Olivia (Patricia Arquette), father Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke), and sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter)

This is a hugely ambitious strategy, and nothing short of a triumph of logistics, but the interesting thing is how modest the movie nevertheless feels. As the film’s collection of vignettes plays out in front of us, there are no obvious time markers beyond assorted pop songs and political references. Sometimes a few scenes can go by before you realize that our protagonist’s hair is a little shaggier, his frame a little lankier. The months and years sneak up on you, and by the time they register, they’re already gone – the wallop here comes only towards the end, as you process the cumulative instances of time slowly slipping by.

The overarching structure of the film is what’s most moving about Boyhood – the content of each scene within it is more hit-or-miss. The strongest scenes in the film actually belongs to Hawke and Arquette as Mason’s divorced parents. Mason Sr. starts out as a sort of archetype, the arrested-development “fun dad” breezing in on weekends to take his kids to Houston Astros games while avoiding more substantive responsibility. But he’s self-aware about the cliche he inhabits, and time mellows out his arrogance and flakiness – when he gets remarried to a woman from a conservative family, he trades in his Pontiac GTO for a minivan, bites his tongue as his conservative in-laws gift his son a bible and a rifle, and nevertheless maintains denial about losing his wild youth.

Olivia, on the other hand, is forced into responsibility as the parent with main custody, as much as she might secretly crave Mason Sr’s freedom – “I was someone’s daughter, then I was someone’s f***ing mother,” she yells during a fight with a boyfriend, lamenting that lost state in-between. She ends up running through a succession of bad marriages with abusive men (these scenes, particularly the ones involving an alcoholic professor played with too-obvious sleaze by Marco Perella, feel jarring in their conventional movie-logic and melodrama, compared to the rest of the film’s more laid-back observational feel). But she survives and makes impressive professional strides, growing from a part-time psychology student into an esteemed psychology professor, lecturing about John Bowlby’s attachment theory.

That theory is about the way parental love molds our emotional development, and how important that factor might be is one of the the film’s persistent questions as we see Mason growing up. As a younger child, he’s quiet and moody – not forming his own personality so much as being buffeted by the forces of family turmoil around him. But that changes as he reaches his teens and becomes self-assured and thoughtful, having absorbed his father’s anti-establishment mindset and resisting modern forces like Facebook. (Mason complains about technology trapping people in an emotionally “in-between” state, and we see exactly what he means during a Skype conversation with his father marked both by Mason’s Sr. deep love but also his inevitable distraction.) It should be said that one of the surprising and refreshing things about Boyhood is just how average Mason ends up being. He’s inquisitive and bright, but not particularly hard-working or sure of a path for himself in life – the movie ends up feeling like a prequel to Linklater’s other films about on aimless youth, Slacker and Dazed and Confused.

Given the inherent power of his premise and method, Linklater seems to occasionally lay it on thick when it comes to underlining his points about growth and the unpredictable ripples of time. There are plenty of elegant and moving images – like when a young Mason, on the verge of puberty and moving out of his first childhood home, paints over the family’s crayon-drawn height marks on a doorframe. But there’s also many that are more blaring and obvious, like the throwaway scenes about a Latino gardener whose life is drastically changed by a brief kind word from Olivia, or the way Mason Sr. explains at length the concept of a Beatles mixtape stitching together solo tracks from all the band’s members.

But none of these moments detract too much from Linklater’s achievement, and indeed sometimes obviousness is even part of the point. Towards the end of the film, Mason and a set of new college freshmen friends wander through a national park, and one friend wonders, with a portentousness that only a stoned amateur philosopher could summon, whether we really can seize the moment or whether the moment seizes us. There’s an obvious banality to that idea, much like the “life isn’t about the destination but the journey” guiding spirit that defines the film’s focus on glancing moments instead of major life milestones. But there’s an obvious truth too. There are a lot of moments here like that, where the wisdom lacking in the advice of blustering authority figures instead slips through from the unlikeliest of sources. The banal is in the profound and the profound is in the banal, since the texture of life is woven with both.