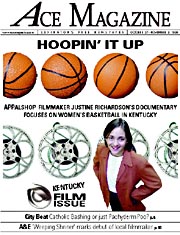

Hoopin it Up

New documentary focuses on

women’s basketball in KY

by Phyllis Sargent

Kentuckians love their basketball.

This is not a newsflash to anyone actually living in the state, but take that statement just one step further: do Kentuckians love their women’s basketball?

The Appalshop documentary focuses on girls’ high school basketball in Kentucky from the 1920s to present day.

Richardson says, “I wanted to tell the history that I didn’t know about, and I think a lot of people didn’t know about, and then I wanted people to think about, ‘What does our society think about sports today and what influences is it having in society that we are so permeated by sports?'”

Returning home to Whitesburg, Kentucky in 1994 after graduating from Yale University, Richardson was looking for a project of her own, and happened upon an idea that combined her love of athletics and film.

“I had just started working at Appalshop. A good friend of mine, Stephanie Wagner Whetstone, who was also working there, was making a videotape about her grandmother, who was a lay black lung advocate. She’d come back from the interview and started telling me about her grandmother talking to her about playing basketball in black sateen bloomers. And we thought that was just the funniest thing.”

Having played basketball herself in high school, the incident touched off memories that eventually led to the making of Girls’ Hoops. Richardson recalls, “At that point, I remembered for the first time since I was in middle school, something that our science teacher and basketball coach told us. The girls’ basketball team at Whitesburg High School was really good-really competitive-and they went to the state tournament. The whole community was really excited and they [the team] were role models.”

Paradoxically, the same coach, despite these memories, also reflected the prevailing attitude of the time. Richardson remembers, “The coach took all the girls aside and told them they shouldn’t play.” The suggestion was, “We should not play basketball because we would lose all our femininity.”

Asked about her stance on the issue of femininity in a traditionally male sport, Richardson replies, “I think it gets misconstrued sometimes as being about trying to be more masculine. It definitely is not a traditional norm; you don’t learn domestic ideals when you are on the basketball court. You learn about competition, strategic cooperation, you learn a lot of things that aren’t molding you necessarily toward a tradtional family life, or whatever that set of stereotypes about women includes. It’s different, but it shouldn’t be coded as unfeminine.”

This gap in the timeline of women’s basketball, especially in Kentucky, became the central theme leading to Richardson’s decision to do the documentary.”It was so striking to me, growing up as a basketball player in the 80s, I didn’t really realize that 15 years earlier, I would not have been able to play. And it seemed like a really important history to share from people’s point of view. How did this happen? And what was it like before? So that was how it got started.”

Girls’ Hoops is a product of community, in all senses of the word. Although Richardson’s research started out small, it expanded, then ultimately shrank back to focus on eastern Kentucky, in the Hazard/Whitesburg area. The film is also a result of a communal effort. She explains, “This project came about, really, over the kitchen table, with Stephanie and I talking about this history, piecing together some things that I had known and heard about. Then, in the research, it became really clear that this would be a good project. First we spread the net really broadly, and we were talking to people all over the state, especially a few people from Eastern Kentucky University who were really instrumental. They became our kind of historian/humanities advisors on the project: Agnes Chrietzberg [editor of the Citizens for Sports Equity newsletter], Peggy Stanaland [professor emeritus EKU, and sports historian], and Judith Jennings [Kentucky Foundation for Women]. Then, as the project moved on we really located it back in eastern Kentucky and ended up focusing on particular women’s experiences there.”

Research is key for any documentary, but Richardson found her difficulty not in finding information, but in deciding what to keep. “One of the first people that I called…was Teresa Isaac. She is now a member of KHSAA (Kentucky High School Athletics Association), and at the time, they were trying to have women referee the girls’ tournaments in the eighties. My mom knew about that and told me to call Teresa. It was amazing. She had these files of things she had been keeping on gender/sports equity, and she pointed us to a number of people. As we talked to her, we found out there were all these women who were keeping the history in folders. They had newspaper articles and pictures, things that they were keeping even though it wasn’t a story they had learned in school.”

“We started off looking for women who had played in the 20s and 30s, Richardson remembers. “There’s a woman named Virginia Combs [Class of 1918] in the film who was an English teacher at the high school for generations of kids in Whitesburg. She told her ‘Shorty’ story to a lot of people, so when I started asking around, they said, ‘You have to talk to Virginia Combs.'”

From another example Richardson recalls, “We started filming in Hazard. We went to film the practice at the gym, and Margaret Boggs came, since her granddaughter was on the team at the time, but she had played. The coach had told her what we were doing, so she came to talk to us.”

As the history began to unfold, Richardson discovered that girls’ basketball was alive and thriving until 1932, when the Kentucky High School Athletic Association decided to cut back on school programs. The Depression era meant less funding for school programs. Oddly enough, only the girls’ programs were cut entirely. Richardson reflects, “I think that’s the big question. I’m sure there are historians who are thinking about that, and how it is that something could be OK for women (or anybody) to do at one point, and it’s really not OK for a long time after that. So how does that happen? There was discussion about women’s health…a lot of it was coming from male doctors. And it was really because women were supposed to be protecting their organs for childbearing and this delicate adolescent time was not a good time to be bumping them around. That’s how it was seen.”

Title IX was passed in 1972, which states in part that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded form participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance”(20 USC Sec. 1681). Richardson says, “Girls’ Hoops deals with girls’ and women’s experiences over time. These changes happened, in large part due to legislative changes. At a time now when there is a lot of debate about whether or not government can make a positive difference in the lives of ordinary Title IX is an example which made a tremendous impact on our society at largeNow we as a society think it’s great that woment play sports and (hopefully) we won’t be able to go back to that previous lack of opportunity.”

But it was 1974 before the legislation had any practical effect. This was when Kentucky state senator Nicholas Baker signed “The Basketball Bill,” and girls’ teams were revived. Richardson reveals, “His mother [Roberta, who is featured in the film] had played. Which goes back to the influence that women were having despite what the dominant situation was; there were women who were pushing for change in the process the whole time.”

The power of women is another reason Richardson wanted to tell the story: “This absolutely to me is cut from a feminist point of view. Basketball is a great hook to talk about girls. People love basketball, and are big fans, but then it [women’s basketball] gets into these other questions and issues. There are lots more films about girls’ basketball to be made. In making a 30 minute film there’s a lot that didn’t get in there.”

The scenes in Girls’ Hoops represent real life experiences, and are there fore not always pretty. To tell the present day side of the story, Richardson “chose three teams and followed them through a whole season, filming games and practices and interviewing coaches.”

She admits, “I went into the project with the idea that girls’ basketball is good for everybody, no matter what. That, at a time when, as girls, we are getting attention for being sexual or attractive to boys, basketball is something where you get attention for what you can do. I think that music, science, etc. do the same thing. So I really went in with this positive, idealistic perspective on it. But as we filmed through the season and talked to the womenand I reflected on my own experience, the apsect of the intensity and the competition really started to stand out as more defining. I realized that you can get defeated by this process, girls just as much as boys. There’s this stereotype of the boy as the football hero who has a hard time later on even though he was so successful in high school. And the same thing can happen to girls if too much focus is put on the competition and winning, rather than on developing into a whole person.”

Richardson is a member of the Board of Directors at Appalshop, and credits the people there and the program with making the film possible. “I really wanted to do a project of my own, but I also wanted to learn. Appalshop comes from a tradition of training, learning in a kind of old-fashioned apprenticeship way, that you work with people, talk about what you are doing, and learn in the process of doing it. Appalshop works as a collective. They have a whole tradition of encouraging young people to do work. I felt really strongly about making a work about my own experiences, and it was really important for me to go back to my hometown.”

She emphasizes her feelings on independent media, “It is really tough for independent videomakers because this is an expensive medium to create and then requires an outlet for distribution there are also a lot of people who are working and struggling on their own to create video and film media from their own perspectives. However, with the unbelievable merging and conglomeration of our national media, it is more important than ever for rural people and independent voices to have something to say and to share with the world at large.”

In the distant future Richardson “will definitely do something on eastern Kentucky again. I’m learning, exploring, I want to do more projects. I want to do more teaching. Maybe a little bit of both, filmaking and teaching.”

Girls’ Hoops, which won a Jurors’ Award, will be shown Nov 3 at 7:30 and Nov 7 at 7:30 at Baxter Avenue Theatres as part of the Louisville Film and Video Festival. For more info on the film, visit www. appalshop.org.

REVIEW

Girls’ Hoops documents women basketball players in Kentucky from the 1920s and 30s, the 1970s, and the 1990s, all told in first person narrative.

It also provides a tour of the eastern Kentucky area where the film is set. Women’s sports in Kentucky was ended abruptly in 1932, supposedly for health reasons, then was reinstated in 1974. That time without girl’s basketball, and what it meant to the women involved, is the central theme of the film. Richardson says, “so that ended up becoming the organizing principle, to look at the changes and the context from the perspective of girls in eastern Kentucky and how that changed. It meant that a lot of coaches, historians, and other people actually interviewed ended up not being in it [but] they certainly informed how the film came to be.”

The sense of community, between the players themselves, and the people that support them, gives heart to the film, making it much more that a “sports documentary.”

Although the film tries to stay away from making judgments, it does raise quite a few questions about the role of women in society. Win or lose, the women featured in the film come across as strong, more concerned about just playing, than in trying to prove a point.

Geri Grigsby, All State, leading scorer, and all around athlete is one example. Her father, a high school principal, admits in the film that at first he never considered his daughter as an athlete, although she played against her brothers at home. At school, Geri was a cheerleader for the boys, thinking inside that “she knew she could do better.” When girls’ basketball was reinstated, Grigsby became the star of her team, made her father proud, and now works as a lawyer in the state Department of Transportation. For her, “just getting to play” was a really important part of her life.

Richardson chose three present day teams and followed them through a season, filming practices and interviewing coaches. The emotions the girls feel as they play the game they love and how they interact with families and peers is integral to the story, and is presented “as is.” Their reasons for playing, and their hopes and dreams for the future sound just plain human, rather than “male” or “female.”

Overall, though, the mood of the film is a celebration of the end of a struggle. Richardson says it best when asked about her strongest interest, athletics or filmmaking. “It’s so hard to divide the two. Are you a woman or are you an Appalachian? Do you love basketball or art? It’s like these combinations that we all are-different aspects of ourselves.”

Girls’ Hoops has won several awards already, including the Silver Star, Houston International Film Festival, and the Reno Award, East Lansing Film Festival. It is scheduled to be broadcast via PBS Plus in January of 2000. It is part of a “Viewer’s Guide” that is being used educationally. Richardson says, “There are some teachers who are using it in classrooms-Sports Sociology especially, but other classrooms as well-we look at either history of the changing perceptions of girls in sports.” -PS

BIO

Richardson is presently attending Michigan State University in the American Studies Program. She graduated from Whitesburg High School, Whitesburg, KY (1988), and attended Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH as part of their outreach program.

She received a Richter Fellowship for travel and research in Italy, then graduated from Yale University, with a BA in History of Art in 1992, where she received the Kellogg Prize.

She is currently working with the Kentucky Domestic Violence Association on a piece about domestic violence, particularly in rural Kentucky. “I am very interested in violence against women, but also violence in society.” It is scheduled to be finished in January. -PS