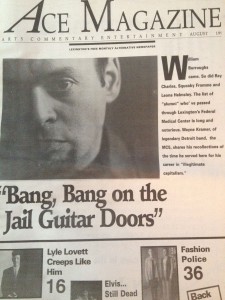

Ace August 1995

BY STEVE POULTON

[three_fifth]

Charlie Parker wasn’t a resident there, but Ray Charles was. Writer William Burroughs came for the cure; so did his son. The list of “alumni” who have passed through Lexington’s Federal Medical Center is long and illustrious.

Presently a low-security prison, the Center was created as a “narcotics farm” in 1935 — designed to rehabilitate inmates addicted to drugs. Wayne Kramer of the legendary MC5 served two years here in the mid-70s for what he describes as his career in “illegitimate capitalism”

Kramer generously shared with us his recollections of his time at the Federal Correctional Institution in Lexington.

“Bang, Bang on the Jail Guitar Doors.”

“PRISON, n., A place of rewards and punishments.”

–Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

A sprawling stone and red brick fortress behind two sky-high razor-wire fences, separated from the road by a circular drive and six hundred acres of freshly cut grass — you may have seen it while walking the dog in Masterson Station Park, or while taking that scenic cruise out Leestown Road toward Midway. I’m talking about the Federal Medical Center, formerly the Lexington Narcotics Farm, the first federal co-correctional facility in the United States built specifically for the rehabilitation of inmates addicted to narcotics.

If you’ve spent much time in Lexington, you’ve probably heard the rumors concerning the famous musicians, writers, and other celebs and their treatment or incarceration at Lexington. No, jazz saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker was never there, according to Ann Diestel, my contact at the U.S. Bureau of Information.

Tenor man John “Zoot” Sims did receive treatment there. (He played with Stan Kenton, Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, and even made a record with beat-writer Jack Kerouac, Blues and Haikus, Hanover HML-5006, if you care and can find it). Trumpeter Robert “Red Rodney” Chudnick, who played with Parker (check out Bird at St. Nick’s, Fantasy OJC-041) was also a patient/inmate at Lexington. Rhythm and blues great, Ray Charles, is said to have received treatment for his decades-long heroin addiction at Lexington in the late fifties.

Writer/junkie William Burroughs (Junkie, Naked Lunch) is another former Narco-Farm patient. His son, junkie/writer William Burroughs, Jr., wrote Kentucky Ham, which details the events leading to his own admission to the facility and contains a memoir of his stay there.

Manson moll Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme and Leona Helmsley are among others who collected their mail at 3301 Leestown in more recent years.

Surprisingly little information exists on day-to-day prison life at the Lexington FCI. I was, however, able to gain some insight from one of the more infamous former inmates.

***

“Have you heard about Wayne, he deals the cocaine a little more everyday…”

–the Clash, from “Jail Guitar Doors”

Wayne Kramer is the former guitarist for the now legendary and highly influential Detroit group, the MC5, whose music combined elements of free-jazz improvisation (a la Archie Shepp, John Coltrane, and Sun Ra, etc) with more traditional and comparatively simple rock-song structures, played at planet-splitting volume. (I play the guitar and the amp,” says Wayne.)

The breakup of “the Five” came after just three records, amidst drug related problems within the band. Wayne was reduced to hustling dope on the streets of Detroit to keep the wolf from the door. And he was using, too.

“Crime is really exciting stuff. After the breakup [of the MC5], I was no longer a star, so to speak, in the world of music. I saw all these other bands like Ted Nugent and KISS become huge. Fuck, my band was so much better than someone like KISS. But there are stars in the drug world too. It was just an easy option.”

Wayne’s career in “illegitimate capitalism,” as he calls it, was even more brief than that of the MC5. Arrested in 1974, Kramer was charged with distribution of cocaine and received a four-year sentence, the last twenty-six months of which he served at the Lexington Federal Correctional Institution. So what was jail like — a day in the life? Brother Wayne kicks it to us thusly:

“[Lexington] had a reputation as a good place to do time. It was pretty much to the left of the spectrum as far as instititutions go. There was more of a focus on rehabilitation than atonement for your crimes. I had a lot of time to think.

“Everybody had to work, if you could work. Some people made furniture, whatever. My job was doing the layout for the prison newspaper they had in there, ’cause I had some artistic ability. I could draw. I did some cartoons and stuff. I got paid $20 a month. That was considered a good job.

“I went to bed around ten. I had a transistor radio and I listened to this college station [WUKY] that played jazz. It would go off the air at like eleven and come back on at seven in the morning and that’s when I would wake up. It was pretty cool actually. I worked five days a week, got off at four in the afternoon. They had ‘count time,’ five times a day. They counted you after lunch, before dinner, again at seven, ten-thirty, and three in the morning. I ran in the yard every night. Seven laps around was a mile, and at the end I was doing like five miles.

“I shared a cell when I first got there. The rooms were like hospital rooms — big heavy doors with a little window. There were bathrooms on every hall and kind of like a lounge, called the ‘day room,’ where we had all kinds of group [counseling], RBT, which was ‘rational behavior training,’ PMA, which was ‘postitive mental attitude,’ ‘transactional analysis,’ and what we called our ‘alley group.’ That was a twelve-step program, kind of like Narcotics Anonymous. That was just for our hallway, but it wasn’t very organized.”

As fate would have it, Kramer’s stay at Lexington coincided with thta of another great musician, the late Red Rodney. As any two musicians with an abundance of free time (and no access to dope) are wont to do, they began to play together. Despite being of completely different musical genres and with an age difference of 25 years, there are similarities in the recorded music of both men.

The music of the MC5, though much more raw and simple in form, is like Rodney’s bebop in that both were highly improvisational and vital music of the times: the MC5’s influenced by the political and social turbulence of the late 60s and early 70s; Rodney’s music reflecting the changes that took place in jazz, via musicians like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Max Roach in the late 40s and early 50s. The spirit is remarkably the same. One can only wonder what it was like to hear Kramer playing wah-wah guitar behind and around Rodney, a technical master of the trumpet and a disciple of Gillespie’s. Kramer swears there are tapes. (We’re waiting…)

“Oh yeah, we had a band in there. Red had been there a couple of times, when they were trying out new cures for morphine and heroin addiction. He said they just stayed [high] all day. Yeah, he recalled those days quite fondly.

“We had a band, me and Red, and whoever else happened to be in at the time. We did a little program every Sunday in the auditorium. We played funk and a little bebop and a lot of blues. There was a great drummer, also from Detroit, named Eric Low. We backed up singers, whatever. There was a black sax player, not an inmate, who would bring his group in there and play with us sometimes. He was a mailman, lived around there. He was real good.”

(I asked Kramer if the sax player’s name could have been Duke Madison. He says it could have been, but didn’t really remember.) “We played in a park there, in the town. That would have been about ’76 or ’77.”

Kramer was released from FCI in the spring of ’78. Red remained another eight or ten months, by Kramer’s account. For the final three months of his sentence, however, Kramer was able to work outside the FCI counseling kids at the Fayette County Juvenile Detention Center.

“It was pretty cool, I got to leave [the grounds of the FCI], eat lunch downtown. Most of the kids had already fucked up pretty bad. It was sad, but I could talk to them ’cause I had been there. Maybe I helped a couple of ’em. A lot of them were paint huffers though. I had never even heard of that. Yeah, jail saved me. It’s not a sore spot anymore. I got out and I’ve been clean since the mid 80s.”

Wayne assured me that these days, he’s “living right.” After years of earning his living as a carpenter in the Florida Keys and Nashville, Wayne has relocated to Los Angeles, is happily married, and is once again, dare I say it, kicking out the jams. He’s been on tour with his band all year in support of a new CD, The Hard Stuff (Epitaph).

[/three_fifth]

[two_fifth_last]

<span style=”color: #ea144f; font-size: large;”>A BRIEF HISTORY OF LEXINGTON’S FEDERAL MEDICAL CENTER</span>

In the early 1920s, America had begun to develop more progressive ideas toward solving its social dilemmas, including that of substance abuse. Narcotic addiction, in particular, began to be recognized as a disease– a social and medical problem, rather than one of a purely criminal nature. Realizing that stiff jail sentences alone were an ineffective means of rehabilitating addicted inmates, Congress passed legislation in 1929 for the founding of two “narcotics farms.” The first, in Lexington, Kentucky, opened in 1935, the second in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1938.

The new Lexington Narcotics Farm was home to the newly formed Addiction Research Center on Drug Addiction and the Addiction Research Center. Here, researchers from the Public Health Service began conducting tests to identify the receptor sites of psychoactive drugs in the human brain and central nervous systems.

Vocational educational programs were created to help inmates find and maintain employment upon re-entering the world as non addicts.

Women were first received at the controversial farm in 1941, making Lexington the first co-correctional facility of its kind. Another of the farm’s distinguishing features was its acceptance for treatment of those addicts who voluntarily admitted themselves for treatment, in addition to the federal inmates already housed there.

In 1974, as the Clinical Research Center at the farm was transferred to the Bureau of Prisons, followed by the Addiction Research Center a few years later, the Lexington Narcotics Farm became a low-security prison. This marked the beginning of a series of transformations at the site from a co-correctional facility to a women’s prison, and back again over the next fifteen years.

[/two_fifth_last]