Ready User One?

‘Don’t Worry Darling’ is a candy-coated Manifesto in pastel sheep’s clothing

With all due respect to Ray Charles, at least two generations of fans will always associate “Night Time is the Right Time” with The Cosby Show (the family famously lip synchs it in a staircase performance celebrating the grandparents’ anniversary). The sexy 1958 classic also sets the scene and opens director Olivia Wilde’s latest, Don’t Worry Darling.

Cosby. That can’t be an accident. “Tease me (night and day). Squeeze me (night and day).”

Setting aside any/all celebrity-controversy surrounding the making of the movie, Darling is, at its core, a prima facie polemic on the battle of the sexes.

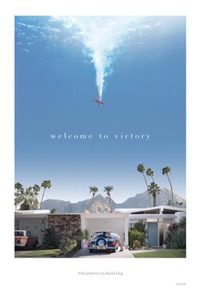

Don’t Worry Darling is set in Victory, a mysterious 1950s-esque company town in an unnamed desert. What is the company? The Victory Project. What is the Victory Project? It might as well be Area 51 for all the wives know. Is it an MLM? Is it Amway? Tupperware? Whisper, whisper, defense, whisper, weapons, whisper. The men drive away from their cul de sac every morning in a synchronized Mad Men-ish pastel ballet to report to a mostly unseen “headquarters.”

Don’t Worry Darling is set in Victory, a mysterious 1950s-esque company town in an unnamed desert. What is the company? The Victory Project. What is the Victory Project? It might as well be Area 51 for all the wives know. Is it an MLM? Is it Amway? Tupperware? Whisper, whisper, defense, whisper, weapons, whisper. The men drive away from their cul de sac every morning in a synchronized Mad Men-ish pastel ballet to report to a mostly unseen “headquarters.”

Jack (Harry Styles) is a “technical engineer” for the Project, married to Alice (Florence Pugh). Chris Pine is the subtly diabolical “Frank” who’s Jack’s boss, and the architect of this “planned” community (or cult). But what is he planning? Nothing good. Is he Piggy, or is he Ralph? Punctuating the action is a series of 1930s Busby Berkeley-style brief visual intermissions that serve as a Greek Chorus that’s equal parts Moulin Rouge and Clockwork Orange.

Wilde herself plays Bunny, a sardonic mother of two who serves as both foil and frenemy to Alice. The wives don’t “work.” The wives don’t drive. They shop, they cook, they clean, and they stay fit and demure at a ballet regime conducted by Frank’s wife, Shelley (Gemma Chan), with genteel authoritarianism. At least Alice has a passionate marriage, with steamy love scenes vividly choreographed in between all the cooking and cleaning and dancing.

But any dystopia worth its salt must have a Cassandra, and Kiki Layne as Margaret, makes it clear to both the audience and the coffee klatch that all is not well in Victory with her cryptic and restrained, but desperate, observations.

It seems only Alice is listening intently to the warnings through the looking glass though, and she becomes increasingly disturbed. Then there’s a twist, where all is made — somewhat —clear. Just what in the fresh Philip K. Dick-ish hell is all of this?

Nothing that happens in Act II will be a surprise to anyone who’s paid attention in Act I, or to anyone who has seen any of the films that Darling pays homage to. There are virtually scene by scene echoes of Gaslight, Stepford Wives, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Matrix, The Firm, Total Recall, Minority Report, Requiem for a Dream, Clockwork Orange, too many Hitchcock moments to count, and even HBO’s two-season series, Made for Love (recently canceled).

Is a film that relies so heavily on tribute necessarily derivative? Surprisingly, no. And that’s no small testament to cinematographer Matthew Libatique, whose visual cues add up to a truly striking visual Hockney-esque feast. The repeated anchor sequence of egg, bacon, coffee interspersed throughout to frame the mornings on Victory’s cul de sac is a direct ode to his work with Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream, in particular).

In fact, one wonders what a more seasoned director like an Aronofsky would’ve done with the material. And, it has to be said, the casting.

Poor Harry Styles is fine as Jack. This is only his second major role, but that lack of experience mostly works for the character. He’s presented as the ingénue here. He’s no Leo DiCaprio in Revolutionary Road, but he’s fine.

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said of Florence Pugh. Although she has received largely rave reviews, those reviews are generally misguided and in some cases inaccurate. She is simply tragically miscast and never seems to be sure whether she’s channeling Kate Winslet or perhaps Elisha Cuthbert (the latter is not a compliment). Everything about her feels anachronistic, and though an argument could be made that this was meant to serve the narrative, it emphatically does not. (The distraction of her bad extensions obviously can’t be blamed on her — someone made that very wrong choice — but they don’t help.) Although a Jennifer Lawrence (at 32) might technically be a bit too old to be persuasive as the young 1950s newlywed, it would have been a pleasure to see her try.

In the end, tune out all the celebrity noise. It isn’t reflected in what we see on the screen, which adds up to an altogether decent diversion as we all emerge from the Covid-era cinematic desert. Is it as strong as last year’s candy-coated feminist manifesto, Promising Young Woman? Probably not, but we have to start rebuilding somewhere, and pastel melodramas like these are a delicious alternative to the relentless return of superheros and green screens threatening to send many of us back to our sofas and Netflix.