Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner James Comer appeared on Kentucky Newsmakers with WKYT’s Bill Bryant to discuss his “full court press” to get the Kentucky General Assembly to support industrialized hemp.

Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner James Comer appeared on Kentucky Newsmakers with WKYT’s Bill Bryant to discuss his “full court press” to get the Kentucky General Assembly to support industrialized hemp.

Comer also appeared at the Lexington Forum on Thursday, January 3, to drum up support.

Comer tells Bryant, “I believe it’s going to be legalized at the federal level at some point this year, and the first few states that get on board are going to be the states that develop the industry. The states that develop the industry are going to obviously have the markets for the farmers, but they’re also going to be the states that create the jobs, and this is what this is all about. Creating jobs in rural communities, and opening up a new market for Kentucky farmers.”

As for prospective products, he says, “In Europe, they’re taking all sorts of products out of the automotive industry that we use here and make from plastic — in Europe, they’re making them from industrial hemp. You can make products in the construction business — where we use wood for plywood here in the United States — they’re using hemp in Canada. If you go in your family’s bathroom, you’ll see cosmetic products in there made from industrial hemp, imported from Canada. We can produce that hemp in Kentucky, and manufacture it in Kentucky. Senator (Rand) Paul is very fond of (supporting) making paper from hemp. If you look at the Declaration of Independence, it was written on paper made from hemp back at that time. It’s much more sustainable and greener to make paper from industrialized hemp than it is from trees.There are a lot of uses for industrialized hemp that other countries are doing — we can do that in the United States. And if we’re going to do that in the United States, which I think we will, let’s do it here in Kentucky.”

Bryant asked, “is Kentucky a good place to grow hemp, from an agricultural standpoint?”

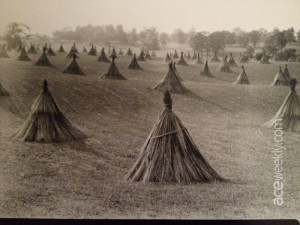

Comer says, “At the turn of the century, hemp was the largest crop in Kentucky, especially here in Fayette County. People think that tobacco’s always been the biggest crop in Kentucky; it was industrialized hemp in the early 1900s. Some of our leading founding fathers of Kentucky grew hemp. Henry Clay grew industrialized hemp. Abraham Lincoln’s wife’s family were big hemp farmers in the Louisville area. It’s a crop that we know grows well here in Kentucky. I met [a man] at the Lexington Forum who said his father and grandfather grew industrialized hemp during Word War II, right here in Fayette County. From an agricultural standpoint, this is a crop that we know will grow well in Kentucky. We know what other countries are doing, as far as creating manufacturing jobs, manufacturing industrialized hemp. So we’ve got a crop that grows well in Kentucky. We’ve got a desperate need to create jobs in Kentucky. If you research industrialized hemp, you see it’s a no-brainer and it’s a win-win situation for Kentucky.

“This crop is gonna be legal. I talk to commissioners of agriculture all across the United States on a daily basis. More and more ag commissioners are starting to push for this. I think we’ve got a step ahead of everybody else. But there are other states like Oregon, Minnesota, North Dakota, that are making the same push that I’m making. Let’s get this bill passed in the General Assembly, and let’s have the infrastructure in place to where when the federal government says this is a legal crop to grow, we’re ready to go and we can create those jobs first here in Kentucky.”

Bryant asks the Commissioner, “what do you say to those in law enforcement who say they cannot distinguish between — particularly when they’re doing surveillance from the air — between industrialized hemp and pot, and they say they don’t have the resources to do laboratory testing on the plants and that kind of thing.”

Comer responds, “people say law enforcement’s against it. I’ve spoken at a Kentucky Association of Counties conference. I did a workshop for the sheriffs. I try to be very transparent with this and make sure everyone has a seat at the table in trying to set this legislation up. I can tell you with certainty that the sheriffs of Kentucky are openly supportive of this. Most of the sheriffs are from rural communities; most of the sheriffs have agriculture backgrounds; they can tell the difference between an industrial hemp plant and a marijuana plant. They know we need to create jobs; our farmers need new opportunities; and they’re supporting it. There are a few in the state police that are against it. I wish they were for it. But I was a state representative for eleven years in Frankfort, and we voted on a lot of legislation. I don’t remember very many times when there was a hundred percent agreement on anything. We’re going to continue to work with law enforcement. We’re going to regulate this, when it becomes legal. The Department of Agriculture is the largest regulatory agency in state government. We have the infrastructure in place where we can regulate it. We want to work hand in hand with law enforcement to assure them that this has been a good thing in Canada. If anything, it’s eradicated marijuana in Canada.”

Bryant asks, “you would track where the tracts are? You would know exactly who is licensed to grow hemp?”

Comer responds, “they will have to register and sign up at the Department of Agriculture. We’ll do a background check, to make sure there are no marijuana growers trying to sneak in the back door and grow industrial hemp. We will also have a GPS map, where every field is plotted. So if the state police are flying in the helicopter, and they see something that looks like marijuana from the field, they can look on the GPS map, that we’ll provide, and if it’s not registered with our department, then they probably need to investigate that.”

Bryant asks, “do you think your efforts are help or hurt by the move out west by some states to legalize marijuana for recreational purposes? Does that mix the message at a time when you’re trying to get this passed?”

“I don’t even like to talk about marijuana and hemp in the same sentence,” Comer says, “because they are totally different crops. The flipside of that is, I think people are beginning to look at the war on drugs, and they realize we have a terrible drug problem in the United States. We have a terrible drug problem in Kentucky. But the drug problem in Kentucky is prescription pain pills and meth. So, when we’re talking about getting tough on crime and fighting drugs, I think the effort needs to be on meth and prescription pain pill abuse in Kentucky. We need to create jobs. We need to get serious about this. We have a lot of problems in Kentucky. Our state is trailing our surrounding states, with the exception of maybe Illinois. We’re not creating jobs. We don’t have a business-friendly tax environment. This is one thing that we can be a leader in. And I hate sitting back and watching the General Assembly say, ‘well let’s appoint a Task Force, and study this, and kick the can down the road for a few more years. This is something we can do now to create jobs (and) generate tax revenue at a time when our state faces a huge pension crisis, and lots of other challenges that need to be addressed.” (Then-Governor Brereton Jones appointed a Task Force in 1995.)

Law enforcement opposed a failed hemp bill in 2000 as well, though the bill’s proponents explained then,

The Kentucky State Police in particular raised red flags – and red herrings – in opposing the bill. In the Lexington Herald-Leader, for example, a police spokesman waxed rhetorical: “What would stop someone from planting two or three rows of marijuana in the middle of a field of hemp?”

The answer is basic botany and economics. Hemp and marijuana, both members of the cannabis family, aggressively cross-pollinate with undesirable results for both. Interbreeding marijuana valued for high THC content with low-THC hemp dramatically lowers THC content and thus economic value of smoked marijuana. Likewise, lanky hemp plants grown for the fiber in their stems would lose those desired characteristics if interbred with bushy pot plants.”

–Ace archive, 2000

The current bill’s sponsor is “Senator Paul Hornback, he is the new senate agriculture committee chairman, from Shelby County. He’s been a leading farmer and a leader in the agriculture community for many years,” Comer says, “and was elected recently to the Kentucky state senate — I believe he’s serving his third year in the state senate. I’m very confident that bill will get a very quick hearing, and pass out of the Kentucky state senate.”

Bryant asks, “have you thought of crafting the legislation in a way that might entice law enforcement by offering incentives to them out of some of the additional revenue that might come in?”

Comer says, no, “but we have invited them to the table. I’ve had meetings in my office. We have the new Industrialized Hemp Commission that has reunited, and is starting to meet regularly, and they have a seat at the table, as do the chiefs of police of Kentucky, and the sheriffs. Everyone has the opportunity for input on the bill, and we want to work closely with law enforcement.”

Bryant doesn’t let the prospect of pork drop. “As an example, the state police want to build a world-class training facility in Frankfort right now. They’d like to have the money to get that done. Have you thought of offering them something out of hemp money to get that done?”

“No,” Comer says, sticking to his guns. “I haven’t. There are a lot of agencies that want to build new buildings and do new things. We have a terrible pension crisis that a lot of the state police and state employees are faced with. I think the number one priority for all those government agencies,and state employees is, we need to do something to enhance economic activity in Kentucky. This is something that will do that. This will create manufacturing jobs, and create badly needed tax revenue. The days of the federal government coming in and doing bail-outs and stimulus and things like that, are over. It’s over. The states like Tennessee and Indiana and now Ohio that are being progressive and reforming their tax codes — not to just generate revenue, but to create jobs, and entice businesses to come in and make an investment in communities — those are the states that are going to be able to build the new police academies. If we keep going down the same road we’re going down in Kentucky, there will be no police academies for the state police. We’ve got to create jobs.”

Bryant asks, “would you see hemp being a Kentucky Pride product eventually?” (Kentucky Proud is the state’s branding program for grown/made in Kentucky.)

Comer says, “we want to take this very slow. We want to make sure that people realize there’s still a lot of misinformation about this. This is not a drug. It’s totally different from marijuana. But I do believe that a lot of people, especially in rural communities, have given up on manufacturing. They say, well that’s gone forever after NAFTA. I believe this is something that will come back and start creating manufacturing jobs again.”

Bryant says, “you’re a professional farmer yourself with an academic background in agriculture, and you said this also could have the effect of weakening the marijuana crop, in terms of its intensity.”

“Exactly,” Comer explains: “If hemp cross-pollinates with marijuana, the marijuana won’t develop a bud, and if it doesn’t develop a bud, the leaves don’t have THC. So if the state police really wanted to eradicate the marijuana plant, they would be encouraging us to license as many people to grow industrial hemp as possible. Because it would wreak havoc on marijuana. Industrial hemp can be marijuana’s worst nightmare.”