Story and photos by Kevin Nance

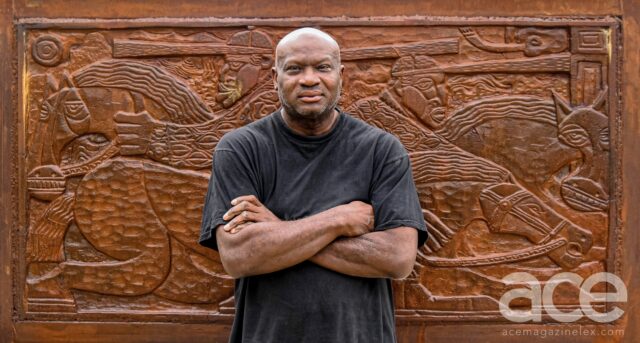

It’s been 21 years since Lexington Artist LaVon Van Williams Jr. first carved a series of wooden relief sculptures depicting the life of Isaac Murphy, the great black jockey from Lexington who won the Kentucky Derby three times in 1884, 1890 and 1891. Five years ago, as Williams was inducted into UK’s Hall of Fame in the College of Arts and Sciences, the Herald-Leader said of the artist, “the most interesting ex-UK basketball player is not in the NBA.”

Now that the work — three majestic double-sided panels with Williams’s signature sophisticated folk art designs cast in metal — was finally installed last month at the Isaac Murphy Memorial Art Garden at Third and Midland in Lexington’s East End, you’d hope that its creator would finally be able to take satisfaction in his long-delayed achievement.

Now that the work — three majestic double-sided panels with Williams’s signature sophisticated folk art designs cast in metal — was finally installed last month at the Isaac Murphy Memorial Art Garden at Third and Midland in Lexington’s East End, you’d hope that its creator would finally be able to take satisfaction in his long-delayed achievement.

But for Williams, at 65 one of the city’s most well-known artists, the moment is bittersweet.

“I’m not displeased with it, but I’m not happy with it,” he says, staring at one of the panels on a recent morning at the Art Garden. “It should look better than this.”

On the positive side, the artwork, as should be plain to almost anyone, is magnificent. “Isaac and Lucy,” which shows the jubilant jockey and his wife celebrating with kisses after one of his Derby wins, their lips and noses pressed together as if any ray of daylight between them is too much, is a freeze-frame of love and triumph. “Race Man,” which collapses time and space by featuring Murphy racing three different Derby horses all at once, is a monument to African-American achievement at one of its earliest peaks.

“My father used to say that Isaac Murphy was probably the best athlete we ever had in Kentucky,” Williams, a former UK basketball forward and two-year starter for Coach Joe B. Hall, says with admiration. “Isaac Murphy is the GOAT [greatest of all time], not Muhammad Ali.”

Kentucky,” Williams, a former UK basketball forward and two-year starter for Coach Joe B. Hall, says with admiration. “Isaac Murphy is the GOAT [greatest of all time], not Muhammad Ali.”

Best of all is the panel called “American Style,” which fractures and recombines the images of Murphy and his races in a complex form of Afrocubism. On one side of the panel, the thoroughbred is suggested by little more than a haunch and an eye. On the other side, a disembodied equine face is stylized in a way that recalls the screeching animal in Guernica, Picasso’s great war painting from 1937 — Williams’s nod, perhaps, both to Cubism and to the violence and spectacle of horse racing. Roses float in the air. At the bottom of the panel under Murphy’s feet, water — a river? an ocean? — washes back and forth. “It represents the people going from Africa to America, from the south to the north in the Great Migration,” Williams says. In one corner, small and fluttering, there’s a butterfly, “which represents rebirth, a renewal of the people.”

When he was a child, Williams says, he’d never heard of Afrocubism, but he noticed the complexity of his grandmother’s quilts. “Her quilts were broken up like cubist art, and that’s what this art here is: a big wooden quilt — a big metal quilt — with the images broken up into different parts.”

It’s that metal part that’s the primary source of Williams’s dissatisfaction. LexArts, which secured a $30,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant to complete the project’s roughly $100,000 funding package last year and shepherded it to completion last month, chose UK professor and sculptor Garry R. Bibbs to do the casting of the metal piece for the Art Garden. Bibbs and Nathan Zammaron, LexArts’ vice president of Community Arts, decided that the work should be cast in iron, the material most in use for public sculpture in Murphy’s own time.

That means that the panels, exposed to the elements, have already begun to show signs of rust, which infuriates Williams. “It’s already turning orange,” he says with anger. “It shouldn’t be rusting. It should have been painted.”

Historian Yvonne Giles, who has been involved with the Art Garden through most of its history, agrees. “I’ve always been impressed with LaVon’s work, so I was glad to see that his designs came to fruition,” she says. “But the reproduction of his original work has problems, no doubt about it. I had anticipated that the panels would carry his signature paint. Everyone knows that LaVon’s work is always painted very vibrantly. But that didn’t happen here.”

history, agrees. “I’ve always been impressed with LaVon’s work, so I was glad to see that his designs came to fruition,” she says. “But the reproduction of his original work has problems, no doubt about it. I had anticipated that the panels would carry his signature paint. Everyone knows that LaVon’s work is always painted very vibrantly. But that didn’t happen here.”

In an interview, Zammaron says it would be “LaVon’s prerogative” to add paint to the panels in the future, but that would require “additional dollars to finance.” In the meantime, he says, “I’ve had multiple sculptors say how much they love the piece. Yes, it will continue to evolve with the elements. But LaVon is a treasure of our city, and for him to have a piece like this, in a material that won’t degrade, is a great thing for us and for him. I think what’s happening is that seeing your work in a new medium — it takes some getting used to.”

Bibbs, who created the 2009 sculpture ‘Lyrical Movement’ for the nearby EastEnd smART art stop bus shelter, agrees. “He’s stuck on the rust thing,” he says of Williams. “Some people can’t wrap their minds around the aesthetic quality of rust, but the piece is absolutely gorgeous, and it’s going to stay that way. People are going to come and take pictures with it for generations to come. It’s going to be historic.”

Williams concedes that part of his issues with the work have to do with the nature of collaboration, which he isn’t keen on.

“Most artists are perfectionists, and when you put out a piece of work, it’s your work — it’s perfect, it’s how you wanted it to look,” he says. “But when somebody else has a hand in your work, it becomes not yours. You’re no longer in control of it. I don’t like bosses, I don’t like coaches — including basketball coaches — because they want to control you. And I like being in control.”

This article appears on pages 10-11 of the July 2023 issue of Ace. To subscribe to our digital edition, click here.