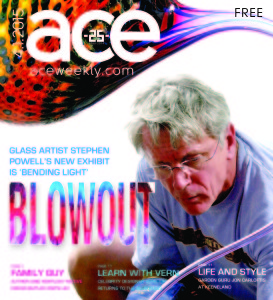

Mind Blowing: Glass artist Stephen Rolfe Powell opens new exhibit in the bluegrass

BY KIM THOMAS

Next time you’re in the mood for a Sunday drive, head out Old Frankfort Pike, and discover the Headley Whitney Museum, a gem tucked into the Bluegrass scenery. If you visit in April, you’ll have the opportunity to see some 43 works on display created by one of the world’s most famous glass artists, Stephen Rolfe Powell.

Next time you’re in the mood for a Sunday drive, head out Old Frankfort Pike, and discover the Headley Whitney Museum, a gem tucked into the Bluegrass scenery. If you visit in April, you’ll have the opportunity to see some 43 works on display created by one of the world’s most famous glass artists, Stephen Rolfe Powell.

The opening reception is being held early on Saturday April 11 to allow guests to get to Keeneland afterwards. The exhibit, Bending Light, will explore the manipulation of light through glass, and will incorporate pieces from Powell’s Teaser, Whacko, Echo, and Screamer series. His vibrant blown glass sculptures are known for whimsical, provocative titles (like Hurricane Lemon Puffer, Brainy Voracious Thrust, Poochy Serpentine Striker).

Headley-Whitney Museum director Amy Gundrum Greene says, “This is Powell’s first exhibit at the Museum, though one of his pieces was included in an exhibit showcasing Kentucky decorative arts last fall.”

Powell’s history of creating beautiful vessels makes the Museum, with its focus on the decorative arts, a logical match.

Powell’s work often turns up in popular locations. This time last Spring, Powell was at work on a commission for Maker’s Mark, now installed at the distillery gift shop in Loretto. You might have glimpsed one of his sculptures at the Denver airport, or at the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga, or at the Zoom In exhibit in Chicago.

When he was putting together the installation for the Aquarium in Tennessee, he compared some of the pieces to jellyfish. He said, “glass is so much like water. When we’re working with hot glass, it’s fluid just like water. When the glass cools, it’s a frozen moment in time.”

Glass blowing is among the most dramatic of visual arts. Watching the process is as mesmerizing as it is intense. It’s much like watching a highly choreographed ballet… and waiting for one of the dancers to break an ankle. It’s tense, fast, and strenuous — one bead of sweat could shatter a piece. (One of the attempts at the Maker’s Mark commission melted when the pipe broke while the piece was still in progress.)

Observers can easily spot evidence of Powell’s early years as a tennis pro in the sheer athleticism of the work.

Part of the process will always be, by its nature, spontaneous. As Powell, who cheerfully describes himself as a pyromaniac, puts it, “One thing I really like about glass, part of it’s under control, part of it’s out of control.”

Whereas the process for completing most visual art is often a solitary endeavor, Powell’s work is team-based, where he is assisted by a handful of students/assistants in the Centre College glass studio he created. It’s a meticulously choreographed routine, one that is loud and exciting.

Powell’s life reads like a script for a movie.

He’s one of the world’s most prominent glass artists, and his career was famously almost destroyed by glass in a 1991 accident.

A window pane shattered as he was attempting to free a bird from his studio space, severing Powell’s tendons, a nerve, and an artery in his right hand.

After a complicated surgery and months of physical therapy, Powell was back at the fire once again.

He says he never considered the possibility that he wouldn’t work again. Initially, he thought he might have to take the night off.

He could’ve continued his career as a designer — allowing others to execute his vision — but he’s passionate about the hands-on aspect of his work.

He recovered, and resumed his work in large scale glass.

In 2004, he took a spill, breaking his left wrist and tearing an Achilles tendon.

That injury and convalescence led him to temporarily make physical accommodations that inspired a new level of creativity, like with the smaller Whacko series.

Catching up with Powell these days isn’t easy. But he spared a few moments while visiting a friend in Venice to tell me a little more about the material he uses to make his incredible glass creations.

I wondered if he prefers sand from one particular area of the world to create his famous pieces, some of which are on display at the Headley-Whitney (the current exhibit will be up through August).

Powell tells me, “The sand we use comes from North Carolina and furnishes the greatest clarity possible for my colors. It is special sand combined with other materials that make our clear glass compatible with my colored glasses that come from New Zealand.”

Powell is smitten with discovering new ways to express himself through the phenomenal world of color.

As he explains in “Vision: The Next 50 Years — The ‘Echoes’ (bowls) are more neutral shapes that allow my focus on the color inside the forms and on the refractions created as light passes through the pieces and lands on the surface below. Another break from my own tradition has been a departure from using a pointillist (murini) approach to exploring color and moving into more linear combinations of color. The influences here are the color field painters such as Kenneth Noland and Gene Davis, along with solar tracking created by stars and moons, such as the moon tracking around Jupiter. Another special influence on these pieces is Lino Tagliapietra who came to Kentucky and helped me develop the Echoes, both technically and aesthetically. ” (Statement for Habitat International 2013)

As he explains in “Vision: The Next 50 Years — The ‘Echoes’ (bowls) are more neutral shapes that allow my focus on the color inside the forms and on the refractions created as light passes through the pieces and lands on the surface below. Another break from my own tradition has been a departure from using a pointillist (murini) approach to exploring color and moving into more linear combinations of color. The influences here are the color field painters such as Kenneth Noland and Gene Davis, along with solar tracking created by stars and moons, such as the moon tracking around Jupiter. Another special influence on these pieces is Lino Tagliapietra who came to Kentucky and helped me develop the Echoes, both technically and aesthetically. ” (Statement for Habitat International 2013)

Many of Powell’s pieces are large — some nearly the size (and price) of a smart car — and the scope and weight of the more enormous pieces do not make his work as an artist easy.

He points out the logistical issues, “While gravity always presents a challenge to working with molten glass, large scale glass is definitely more difficult to work with. We are working with glass that is over 2000 degrees F, so it is always a challenge.”

In his essay, Glass As Painting, Powell talks about his evolution in his method of combining color to create dramatic art. “Viewers used to seeing my pointillist approach to mixing and exploring color with thousands of murrini might be asking, ‘Where are the murrini?’ My answer is that I have zoomed in for a microscopic view of the interaction between targeted color and light…I am breaking color up rather than combining colors. At least some of this exploration of color can be attributed to my fascination with the color field painters of the 1960s and 1970s such as Kenneth Noland and, in particular, Gene Davis. Their linear mystic voyages continue to intrigue and inspire me.”

“We call these pieces ‘echoes’ because we are as concerned with the refraction of color bouncing off of the surface behind the piece as we are with the surface of the actual piece of glass.”

Staying at Centre affords Powell the necessary access to a crew that is a critical component of glass work. “What I do is definitely a team effort,” he acknowledges. Some of his top students have gone on to careers in glass. Brook White started out at Glass Works in Louisville and now owns Louisville’s Flame Run. Former student Che Rhodes is now the head of U of L’s glass program. A 2007 Louisville exhibit included work by 14 artists who apprenticed with him. Another at the Kentucky Artisan Center in Berea also included former students.

Not all go on to careers in glass, but many stay in touch. Former student, Danny Noll, enlisted Powell in proposing to his bride last Spring. The two had both taken undergraduate glassblowing classes with Powell, and missed the process. Noll and Kasey Jackson arrived at Powell’s studio for what was ostensibly a demo and a videotaping of glassblowing alums. Powell’s team had successfully melted “Kasey, will you marry me?” onto the surface of a sculpture. (She said Yes, and the wedding is planned for this June.)

Powell says they caught him in a “Cupid moment.”

“The exhibit ‘Bending Light’ featuring the work of Stephen Rolfe Powell is on display during museum hours through August 9th. The Museum is open Wednesday-Friday 10am-5pm and Saturday & Sunday noon-5pm.There will be an opening reception at 11 am on Friday April 10.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1951, Stephen Rolfe Powell studied painting and ceramics and received his B.A. at Centre College in 1974. Before attending graduate school at Louisiana State University, Powell spent several years as an art instructor, first at the Draper State Prison and later at the Indian Springs School in Alabama. Between 1980 and 1983, he attended LSU and earned a Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics, where he first fell in love with hot glass. His daily life revolves around it, whether he is teaching glass at Centre College or producing his own work.

Powell exhibits his work nationally and internationally. He has worked in Russia, Ukraine, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan and demonstrated at multiple Glass Art Society Conferences, as well as the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Powell’s greatest ongoing legacy is his work at Danville’s Centre College where he has taught since 1983. Originally hired to teach ceramics and sculpture, he founded a glass program at Centre by 1985. The first studio lived on top of the Norton Center for the Arts. Setting his sights on “bigger and better,” Powell designed and completed a state-of-the-art glass studio, which Centre opened as part of their new Jones Visual Arts Center in 1998.

Many graduates of the program have continued on to graduate school and have become successful glass artists. Powell has been awarded Kentucky’s “Teacher of the Year,” honor and has received the Acorn Award from the Kentucky Council on post-secondary Education. In 2010, he received the Governor’s Award in Arts as Artist. Recently, he was presented with the Distinguished Educator award from the James Renwick Alliance in Washington, D.C.

Stephen Rolfe Powell: Glassmaker, was published by the University Press of Kentucky in 2007.

This article appears on pages 6-7 of the April 2015 print issue of Ace.

For more Lexington, Kentucky arts, food, culture, and entertainment news, click here to subscribe to the Ace digital e-dition, emailed to your inbox every Thursday morning.