Method and Madness

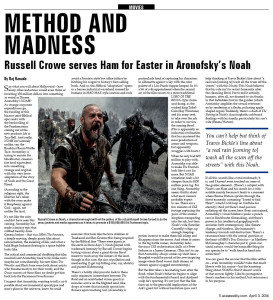

Russell Crowe serves Ham for Easter in Aronofsky’s Noah

BY RAJ RANADE

Say what you will about Hollywood – how many other industries would even think of investing 150 million dollars into something as weird as Darren Aronofsky’s NOAH? As strange corporate expenditures go, the funding of this bizarre semi-Biblical epic ranks with the bankrolling of the Frankensteins coming out of the new products lab at Taco Bell. And really, NOAH isn’t entirely unlike, say, the Breakfast Bacon Waffle Taco. Aronofsky is trying to mutate the blockbuster, cinema’s fast food equivalent, into something strange and original with this very loose adaptation of the story of Noah and the Great Flood.

(According to the religious right, the liberties he’s taken with the story make it blasphemy against God – again, not unlike the taco).

It’s not like the suits couldn’t have seen this coming. Aronofsky has made a fantasy epic that cribbed heavily from Genesis before – that was 2006’s The Fountain, a deeply moving, deeply goofy film about reincarnation, the meaning of life, and what a bald Hugh Jackman floating in a space bubble looks like.

The critical and commercial drubbing that film received sent Aronofsky back to his indie roots (maybe not coincidentally, his next films The Wrestler and Black Swan were both about artists who became martyrs for their work), and the Oscar success of those films no doubt got him back into the Paramount boardrooms.

I suspect that Aronofsky, wanting to tell a sci-fi parable about environmental apocalypse and man’s place in the universe, knew he could avoid a Fountain-style box office failure by hitching his wagon to history’s best-selling book. And so, this Biblical “adaptation” opens in a barren industrial wasteland roamed by humans in MAD MAX style couture and rock monsters that look like the love children of Treebeard and Ben Grimm (this being inspired by the Biblical line “There were giants in the earth in those days”). Noah (played with trademark intensity by Russell Crowe) begins having visions about a great divine flood meant to wash away the sinners of the land, though in this case, the sins of pollution and meat-eating (!) get top billing over, say, idolatry and parent-dishonoring.

There’s a boldly idiosyncratic look to these early sequences (somewhere between The Road and an acid-fueled vision quest) as miracles arrive on the blighted land, like drops of water that instantly sprout into flowers upon touching soil. (Aronofsky is particularly fond of capturing his characters in silhouette against a sky with the color palette of a Lisa Frank trapper keeper) So it’s a bit of a disappointment when the second act of the film resorts to a more traditional Lord of the Rings-style sturm und drang, as the wicked king Tubal-Cain (Ray Winstone) and his army seek to take over the ark in order to survive the coming flood. (His is apparently an industrial civilization that has mastered the mass production of armor and weapons, but apparently struggles with boats.)

When he only had $35 million to play with, Aronofsky was able to make The Fountain look like it cost far more. But Noah sometimes feels a lot cheaper than its $150 million price tag. For one thing, Aronofsky seems thrifty about what most viewers probably expect to see. There are a few minutes of CGI footage capturing the pairs of the animal kingdom stampeding into the ark, but then Noah’s wife (Jennifer Connelly) whips up enough sleeping-potion incense to make them fall asleep and disappear from the movie. And when it comes to the big battle scenes, Aronofsky lacks the mass CGI orchestration skills of a Peter Jackson or a James Cameron. (This isn’t to say that Aronofsky always comes up short here – Brueghel would be proud of the awe-inspiring image where flood waves dash dozens of sinners against a jagged mountaintop.)

But the film takes a fascinating turn after the flood, when Noah’s behavior begins to align with the fundamentalist beard and skinhead scalp he’s sporting. It’s not just that the film faces up to the genocidal implications of the Ark’s guest list without hesitation (you can’t help thinking of Travis Bickle’s line about “a real rain [coming to] wash all the scum off the streets” with this Noah). This Noah believes that his role isn’t to restart humanity after the cleansing flood, but to end it entirely; humans, after all, are doomed to sin thanks to that forbidden fruit in the garden (which Aronofsky amplifies the sexual overtones on by rendering as a fleshy, pulsating apple-shaped organ). Suddenly, there’s a dash of The Shining in Noah’s claustrophobic ark-board dealings with his family, particularly his son’s wife (Emma Watson).

If all this sounds like a total mishmash, it is, and I haven’t even touched on some of the goofier elements. (There’s a subplot with Noah’s son Ham and his search for a wife, notable mainly because it leads to a moment where Emma Watson sprints through the forest earnestly screaming “I need to find Ham!”, which I will loop on YouTube for eternity.) And yet there’s mad passion radiating off the screen here. Even constrained, Aronofsky’s visual boldness packs a punch rare in blockbuster filmmaking, and there’s power in his intellectual grappling with anxieties both contemporary, like climate change, and timeless, like humanity’s tendency towards self-destruction. There’s a resonance here with the central question at the heart of HBO’s True Detective – as Matthew McConaughey’s character put it, given our sinful nature, would the honorable thing for our species be to “walk hand in hand into extinction?”

You can guess the answer that the film settles on – even Aronofsky wouldn’t take that much liberty with his source – but the haunting thing about Noah is that it doesn’t arrive at that answer lightly. Like his protagonist, there’s madness in his method, but seriousness in his purpose.

This article also appears on page 11 of the April 3, 2014 print edition of Ace.