by Bianca SpriggsYou old black gold, you’ve taken my lung/And your dust has darkened my home/And now that we’re old, you’re turnin’ your back/Where else can an old miner go?—Jean Ritchie, Blue Diamond Mines

by Bianca SpriggsYou old black gold, you’ve taken my lung/And your dust has darkened my home/And now that we’re old, you’re turnin’ your back/Where else can an old miner go?—Jean Ritchie, Blue Diamond Mines

“That was the last piece he ever made and I watched him make it,” I am standing next to Bob Morgan in the intimate quarters of Institute 193 at the opening of one-half of the first Charles Williams solo exhibit. Over the bent heads of gallery-goers invested in a motley assembly of pencil holders, Bob is pointing at the only framed work in the room, a handful of pieces so desolate to look upon, they are flinch-worthy. Small wonder most people seem more absorbed in the bright, amorphous pencil holders and t-shirts for sale screen-printed with images from Williams’ drawings.

Behind us, printed in bold type on the wall, are the artist’s own words regarding his life and livelihood, entitled, “My Autobiography,” excerpted from the anthology Souls Grown Deep, Volume II: African American vernacular art, and comprised of interviews and correspondence with one of his primary patrons, William Arnett of Atlanta, in 1995. Surrounded by the remnants of Williams’ work along with his visage flashing across a screen at the rear of the gallery: here throwing up a two-fingered peace sign on the porch of “Silo #3,” his Lexington domicile, and there, swathed in an immense American flag, a gaunt specter of himself, I remember that the man whose phantom we now channel, essentially starved to death after being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS at less than a hundred pounds during the late 1990s in Lexington.

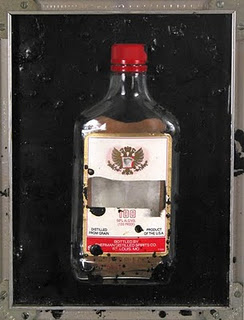

The “last piece” Bob is referring to, a single empty Tvarski vodka bottle welded into a bed of tar framed by blunt, unadorned metal, altogether about the size of a sheet of paper, stands apart, not just because it is one of the only framed pieces, but because it epitomizes such immense isolation in comparison with his other works. Amidst the surge of bright colors and textures of the pencil holders which indicate a predisposition towards process, consistency, dynamism, lucidity, and intent, the tar pieces convey a sense of sporadic yet compulsive creation, swiftly executed attempts at communication, like match flames during daylight when you’ve run out of signal flares.

They are Williams’ rendition of survival, final impressions from the deep end of the human condition that loom with resignation and an eye towards inevitability. They are lonely and distant works that might as well be wailing aloud in the voice of an old, blind blues-singer, “We gone way past rock bottom. Way past coal bottom. This here? This here is tar-pit bottom.”

I don’t understand about diamonds and why men buy them/What’s so impressive about a diamond except for the mining—Fiona Apple, Red Red Red

Bob Morgan was one of Williams’ closest compatriots while he was alive, “Charlie grew up in the Blue Diamond coal camp with his grandparents isolated from the whites and outside sources of influence he relied on his grandmother’s old ways. The family had lived isolated for generations, so there was a clear path to Africa in Charlie’s childhood.”

Perhaps it is no mistake Charles Williams was born in Blue Diamond, Kentucky in 1942, a town named for a gem wrought by some of the harshest environmental conditions on Earth. Eight miles down the road from Hazard, the “big town,” it was in Blue Diamond where Williams, born into a family of miners, would forge a life-long affair with his artistic gift beginning with learning the qualities of mud baked by the sun, which he mentions in his correspondence with William Arnett, “I discovered art making in Blue Diamond coming up, playing house with some of the girls there, which was making mud pies, and I accidentally figured out ceramics, of which I did learn that the mud would get hard like a rock when it dries. I started experimenting with mud, made stuff like head figures out of balls of clay, then let it dry in the sunlight, if the sun did come out.”

After some years up through high-school spent in Chicago with his mother and great-uncle, Williams returned to Kentucky and never called anywhere else home after an automobile accident broke his leg, “It seemed I was meant to be penned into Kentucky, ‘cause every time I got ready to go, something would happen, a little stuff here and there and whatever.”

Williams joined the Job Corp in Morganfield and graduated in 1967 after being trained in technical fields and working as an artist, but ultimately, for all his preparation, ended up employed as a janitor for IBM where he continued making art with the materials he had at his literal disposal, “Plastic melts off the machine and it takes certain forms when it hits the floor. It becomes solid with weird shapes. I put them on a stand and paint it, keep it in its unique weird stage, and some of them forms looks like a animal’s brain. Makes you think of a brain.”

But according to Morgan, it wasn’t just the pencil holders that occupied Williams’ off-time, “He was a super cool personality on the streets of Lexington in the 70sand 80s. You could see him at night in the bars and nightclubs in his lime green pimp suit, a dashing man of color in the daytime in his yard or on his front porch doin’ his thing. Charles’s thing was creating art, raising hell, questioning the cosmos and having a loud classical music experience in the hood. Charlie’s house was covered with propellers and loud splatters of paint. His trees were painted and hung with large cut-outs of superheroes. He built a campfire in the yard to melt tar and amazingly went unnoticed by most in his community.”

Inside the Land of Tomorrow gallery space, a nondescript building on East Third, in what appears on the outside more speak-easy than art gallery, Creative Director and UK Assistant Professor, Dmitry “Dima” Strakovsky and Phillip Jones, Creative Director of Institute 193, call this half of the exhibit more of a celebration of Williams’ work.

Here, the first thing you notice is the nine-and-a-half foot painted wood cutout of Batman alongside highly-stylized renderings of Superman and Dick Tracy. In the excerpt, “My Autobiography,” Williams insists he was painting and sculpting things he thought about, and not from any particular source of emotion.

If that was his claim, then the interior of Williams’ thoughts must have been part Carnival, part mad-scientist’s lab, part dark ride, part Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), and part Sun Ra’s Space Is the Place (1974). Painted found-objects sprout and bloom from the walls and pedestals all over the room, smaller pieces alighting on larger pieces turning a hodge-podge collection of welded and cobbled together items into a motionless orbit as precisely arranged and delicate as celestial bodies in a galaxy.

There are the more prominent and mystifying sculptures like the bulky “Time Machine” and a three-foot red and metallic, slightly phallic pencil, angled towards the ceiling. And then there are lamps, mirrors, birds, propellers, wires, and pipe all layered over and around one under like love-vines, a wild array of color that on the one hand feels as though it’s been applied with reckless abandon, but also a kind of controlled chaos. In the Land of Tomorrow, the breadth of this portion of the exhibit seems much more like pointed commentary on the nature of the cosmos.

After awhile, the work becomes too personal, and makes applying terms like “vernacular” or “outsider” art about as comfortable as wearing a stranger’s underwear. Williams’ work feels precious despite its chaotic appearance and especially vulnerable when you consider how, according to Morgan, the city essentially threw his belongings into the street after he died.

“You mean I am not marked for death?” I asked. I could not help it.

“No. You’re marked for Life.” He capitalized the word—Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

In the origins section of the Moveable Feast Lexington website, the first line reads, “The idea for Moveable Feast Lexington was born earlier in 1998 after a destitute artist with AIDS starved to death just a few blocks from City Hall.” There is next a mention of the activists who ferried food to patients diagnosed with HIV-related illnesses. This number includes arts enthusiast, the late Michael Thompson.

Morgan asserts that this destitute artist who served as the catalyst for Moveable Feast Lexington was Charles Williams, “Much of his work was acquired by the Arnett Souls Grown Deep collection in Atlanta. Charlie could not sell a drop in Lexington. The Arnetts showed Charlie’s work in an exhibit at City Hall in Atlanta for the opening of the Atlanta Olympics. Charlie attended the opening then came back to the poverty of his Lexington life. The next year Charlie went to the UK Med Center with stomach problems where he was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Without family or resources, Charlie went home to make art. Several AIDS activists struggled to help care for Charlie—he wasted fast with no utilities, no money, no food, no hope. At ninety pounds he went back to UK Med Center and died.”

While it may be a natural impulse to romanticize the fact that Williams remained an artist to the end, and it’s easy to conjure an image of him stirring hot tar over an open fire in his front yard surrounded by his painted trees and propellers, the circumstance of his death which led to such dire last works is tragic and real and there is nothing romantic about neglect. Perhaps enough time has passed where we can celebrate Williams’ art posthumously, but regrettably, we must remember that general community disinterest, with the exception of the few people closest to him, was what ultimately killed Charles Williams, moreso than any vice or disease.

There are two very important decisions an artist will make at some point in their development. The first is when inspiration slinks through a crack in the floor as both gift and curse, as seductive opportunity and inevitable reinvention—an artist chooses to not only notice, but to widen the crack. Next, the artist must decide, in an ever-revolving carousel of interests and experiences and drafts and final products, if they are willing to let the last piece they ever touch be worth dying for, because one day, it could potentially be the last work they are remembered by. Today, Charles Williams is being remembered, thanks to the efforts of the Arnett Collection and the Kentucky Folk Art Center for preserving the majority of what was left of his work, Phillip Jones who brought the artist’s vision back home in this comprehensive solo exhibit, the folks at Land of Tomorrow for providing an additional facility for a multi-venue show, and to Bob Morgan who very likely remembers Charlie better than most.

I got me this place here and decided to do something with it. I have always had art on my mind and wanted to do something…that I hadn’t heard of no other person doing—Charles Williams, 1942-1998

Imagine you’re in the middle of your work day, counting down until lunchtime or happy hour. You look up from whatever deadline is pressing its thumb between your shoulder blades, sensing a presence at your desk. A brother in a custodial uniform is standing there holding a brightly painted mass of…something.

Whatever it is makes a jarring contrast to the harsh fluorescents overhead, but you can’t seem to look away. The object seems solid, vaguely resembling the shape of a brain or enlarged organ. Holes have been bored into the surface and a few pencils, a couple of pens, and a highlighter stand at attention like porcupine quills or alien antennae. The brother is cradling it in the crook of his arm, like a pet, like a live thing. You half expect it to squirm in his grip.

He smiles. He has your attention now, “Need a custom-made pencil holder? Fifteen dollars.”

Charles Williams and Silo #3 Exhibit

October 7-November 27

Institute 193 is located at 193 North Limestone Street in Lexington, Kentucky. The gallery is open Thursday – Saturday from 11AM-5 PM and by appointment. To make an appointment outside of normal business hours, contact Phillip March Jones at phillip@institute193.org.

Website: http://www.institute193.org/

Land of Tomorrow is located at 527 East Third Street In Lexington, Kentucky. For questions, or to make an appointment, contact Angela Torchio at angela@landoftomorrow.org.

Website: www.lotlex.com