Policing free speech

No arrests, but protesters felt police presence at VP debate

By Alex De Grand

Major media rushed to crown the October 5 vice presidential debates in Danville to be a triumph as if it were a latter-day matchup of Lincoln and Douglas.

And by some measures, the event could be rated a success. Despite the descent of a national political circus on a small Kentucky burg, no one was arrested, the debates went smoothly, and the town was left standing largely in its original condition.

Yet the event preparations raised some serious questions about free speech.

Some of those who went to Danville to peacefully protest the exclusion of third party candidates from the debates are charging law enforcement agencies harassed them in anticipation of the event. And the ACLU is considering a challenge to ordinances  enacted by Danville to regulate free speech.

enacted by Danville to regulate free speech.

The ACLU had already intervened on behalf of death penalty opponents to see that the Danville ordinances did not prevent their march.

Following the violence that erupted out of protests in Seattle last fall, no public official wanted to see Danville get out of control. And perhaps these Danville activists are exaggerating an episode that was uneventful by many accounts.

But maybe there was something more going on outside the eye of major media. After all, this has been a highly-charged political year featuring Republican and Democratic national conventions marred by questions of compromised civil liberties.

And nationally, observers note the increasing militarization of police power abetted by a Supreme Court shifting more authority to law enforcement.

Long arm of the law – UK style

By late morning on October 5, approximately 100 people milled about “Speakers Park,” an athletic field set aside by Centre College for protesters largely out of view from those participating in events related to the major two-party candidates’ debate.

Despite some grumbling that the experience was like being relegated to the children’s table at a family Thanksgiving dinner, activists were taking advantage of the public address system and stage provided at the site.

Speakers for the Kentucky Green Party, including vice presidential nominee Winona LaDuke, denounced their exclusion and spelled out a number of the issues they would have brought before a national audience.

Sara Todd, a University of Kentucky student activist, noted that she recognized a UK police officer – Det. Joseph Monroe -in plain clothes taking pictures of the proceedings.

Student activist Sara Todd noticed a UK

policeman taking pictures of protesters at Centre.

“The fact that he followed us to Danville – that’s ridiculous,” said Todd.

Todd spoke to Monroe for a few minutes and then he left in what appeared to be an unmarked police car.

“Our society norms and values are changing regarding risks and safety. You can justify almost anything under the auspices of safety. In that kind of normative context — with such a risk aversive society — there is not as much concern if police take extreme measures.” — Peter Kraska, professor of criminal justice and police studies at Eastern Kentucky University.

UK police referred questions to Joseph Burch, the vice president of university relations. Burch did not return calls for comment by press time.

What do they know and how did they know it?

Ken Sain is a political newcomer, making his first bid for public office as the Green Party’s congressional candidate in Kentucky’s fourth district.

Before wading into electoral waters, Sain had a promising career in journalism with stints at several prestigious newspapers including the Arizona Republic, the Los Angeles Daily News, and the Cincinnati Enquirer.

With that background, Sain acknowledged how difficult it is for some people to believe what activists are alleging.

“When you’re a journalist, you tend to blow off [such stories],” said Ken Sain, a Green Party candidate for congress in the fourth district. “Then it happens to you.”

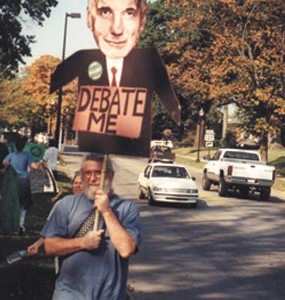

Activists march on their way to hear Winona LaDuke speak outside the debates.

According to the Herald-Leader, the retired agent and Centre officials were “concerned” about the message.

Sain said that message wasn’t posted on a website; it was in an e-mail he sent to a national listserve that, he suspects, law enforcement agents may have broken into.

“Last summer we were talking about Danville and what we might do. It was more a brainstorming session,” Sain said. “I had never been to Danville at that point. I asked someone who had, would it be possible, with enough people, to shut down the college and keep people from getting in and out.

“This person responded, ‘Ken, with enough people we could shut down the whole town.’

“I repeated this conversation on the national listserve, hoping to get enough people interested to come protest with us. That never materialized. But, I have no doubt since I sent that e-mail to the national listserve that was referred to in the Herald-Leader story, that the Secret Service now has a file on me.”

Sain added the retired agent and Centre officials misunderstood the message.

“By shutting down, I – and I’m sure the other person – were thinking nonviolent protests like sit in and possibly blocking streets,” Sain said. “However, the [Herald-Leader] reporter said Danville security was thinking we might have something more extreme in mind. If they knew anything about the Greens, they would have known better. So, I think that will be their excuse for spying on us.”

Other activists relate similar stories raising questions about how much the police know and how they came to know it. Some said they have put false information on their listserves to lure police down blind alleys.

Activists rented this storefront in Danville to serve as a staging area.

Calls made to the Secret Service for comment were not returned.

Bad boys, bad boys

Gary Cordner, the dean of Eastern Kentucky University’s College of Justice and Safety, said police departments are living in a post-Seattle world.

Last year, protests at a World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle turned ugly when some protesters became violent and police responded in kind.

“My general sense is that police departments all across the country got a real shock from events in Seattle,” Cordner said. “Since then – certainly with big events like the protests in Washington D.C. and the two national political conventions – they have taken the possibility of civil disturbance much more seriously.

“In essence, a lot of them got scared and I don’t mean that in a negative way,” Cordner said. “No department wants to be known as the department that couldn’t handle [an event].”

But besides the effect of recent history, there is a long-term national trend toward more aggressive policing based on a military model, according to Peter Kraska, an EKU professor of criminal justice and police studies.

Kraska said this “militarization” of policing originated with a stepped-up drug war, but he explains the movement has since taken on a life of its own.

Policing following a military model means a shift in tactics and mentality, Kraska said.

For example, there is a greater emphasis on instilling order through force, he said. Police use language such as “occupying territory” and “weeding” neighborhoods, Kraska said.

Kraska said there is a growing “paranoia in policing where so many different police departments are seeing more and more things not just as a potential threat, but as a serious threat.”

Extending the military metaphor, Kraska said police tend to approach these threats with something amounting to a “counter-insurgency approach” that includes greater surveillance and arrest tactics.

Accusations like those brought by the Danville protesters don’t particularly surprise Kraska.

Kraska’s research finds police departments are increasingly employing SWAT teams and even small town police forces are treating their crime as if it were a big-city problem. He dubbed the latter phenomenon “militarizing Mayberry.”

Over the years, the Supreme Court has issued rulings allowing police more discretion and authority. Kraska added there is an accompanying trend in society that makes greater police authority acceptable.

Fashionable threads

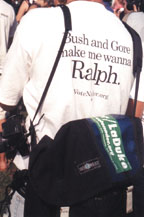

This presidential year has provided numerous opportunities to see how cities and their police forces handle large events that are virtual protester magnets.

Consequently, the ACLU has been busy.

During the Republican National Convention, Philadelphia established a “free speech zone” as the only area protest groups would be allowed to speak for 50 minutes at a time. The city yielded control of virtually all the city’s other public spaces to the Republican Party, the ACLU charged.

The ACLU filed a federal lawsuit when Philadelphia refused to issue permits to two protest groups planning a march and rally in a public space. Shortly after filing suit, the city issued the permits, the ACLU reported.

When the Democrats pulled into Los Angeles for their convention, the ACLU successfully defeated in court that city’s plan to corral protesters in an area far away from cameras and conventioneers.

The ACLU filed suit again to get a restraining order against the Los Angeles Police Department’s behavior toward protesters.

Protesters at the Democratic event maintained a headquarters that the ACLU charged police were subjecting to heavy surveillance and visits without warrants. Individual protesters were being harassed by police through selective enforcement of traffic laws and residents living near the headquarters were asked to spy, the ACLU alleged.

When presidential events shifted to Danville, protesters turned to the ACLU.

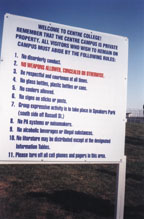

Danville’s city council passed ordinances in anticipation of the vice presidential debates that raised concerns among activists.

Jeff Vessels, executive director of the Kentucky ACLU, said his group intervened on behalf of The Kentucky Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty when the new ordinances threatened to block that group’s planned march.

“Through informal discussions, we were able to work it out for that immediate need,” Vessels said.

But Vessels said his group may not be done with addressing Danville’s new ordinances. He said there are concerns that parts of the ordinances may be overly broad.

Although the debates are over, those ordinances remain in place so the ACLU may challenge them, Vessels said.

The Eleven Commandments

As that old truism holds: Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you.

“My general sense is that police departments all across the country got a real shock from events in Seattle. Since then — certainly with big events like the protests in Washington D.C. and the two national political conventions — they have taken the possibility of civil disturbance much more seriously.” — Gary Cordner, dean of Eastern Kentucky University’s College of Justice and Safety.

Area activists can’t conclusively prove police are spying on them, but they are taking precautionary steps anyway. Recalling the 1960s and 1970s when the government seemed to have a file, a bug or a spy for everyone and everything, many report they avoid e-mail systems and phones they suspect police are monitoring.

One person complained police are acting too much like the KGB.

But, as the protesters ruefully point out, this is not Russia. It is very much contemporary America where fears about crime and violence seemingly outweigh thoughts about preserving personal freedom.