The Delicate Edge of ‘Communality’

Putting the community back in organized religion

by Mia Braden Clark

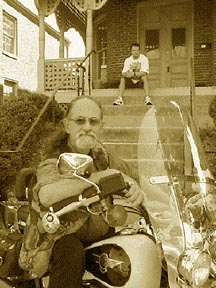

John Smith (above) arrives on a Harley-Davidson, sporting red leather boots and a pony tail in his long gray hair. When the director of a newly formed spiritual outreach program speaks, one hears the lilt derived from a lifetime spent

Down Under, “Why don’t we have a seat while we wait for my mate (his co-director).”

Down Under, “Why don’t we have a seat while we wait for my mate (his co-director).”

As it turns out, he’s also a Methodist minister, though he doesn’t like the connotation that accompanies such labels, “I’m a Christian, but I’m scared of that word.” If Smith shies away from being defined by the church, it is not because his faith isn’t important to him. “You can certainly say I’m a follower of Jesus, and I take that seriously.”

In fact, Smith’s spirituality plays a fundamental role in who he is and what he does. He started Communality about a year ago, having come to America in ’95 to earn a doctorate in cultural anthropology. Though still fairly new, the program has begun to make an impact on Lexington similar to the one Smith made in Australia.

Back home, his involvement in the communities surrounding Sydney and Melbourne was impressive, ranging from programs to counsel car thieves to visiting high schools to rehabilitating prisoners to running the God’s Squad Christian Motorcycle Club.

So what exactly does he do here? What is Communality?

There are few scheduled programs, though the house on High Street is always open on a Friday night, and there is a reading and discussion of passages from the Book of Mark on Sunday evenings.

The house is a good place for talking, relaxing, but to Smith, going out into the town is more important. “True believers should be out in the world, not out there to add another scalp to their gospel belt,” he says, and acknowledges that he and his partner, Greg Leffel, probably spend less time in the house than out of it.

What they are trying to do, essentially, is aid people in any way they can, be it by helping a homeless person get back on his feet, or by chatting it up in Tolly Ho with someone who looks like all they need is a receptive audience.

But don’t expect Smith or Leffel to come knocking at your door at sunrise tomorrow morning, wielding Bibles. Aside from the house not being “a place where you’ll get high pressure tele-evangelism,” Smith’s theology is as alternative as his appearance. Not at all unaccustomed to using bars and pubs as means through which he could aid the individual or community in Australia, he has already started Lexington on a similar track.

An active music and arts scene are cited by Smith as ways to delve into the life of the community, and the house has felt the vibration of several bands since his arrival. Already, he is speaking in terms of clubs. Leffel laughs, mocking, “That’s just what we need; a hundred and fifty freaks like you riding around on Harleys.”

The goodnatured wise cracks are intermingled with reflection. Smith’s unwillingness to label himself is recalled when he reflects, “How much spirit in the hearts of people is wounded by those who call themselves Christians?”

He ponders why “people in the South hate their church,” and yet find themselves the next moment “weeping over a Guinness about a religious experience they had when they were little.”

Consequently, Smith delves into a discussion of what the church, in its traditional sense, might be lacking. “A church can’t address this generation unless they’re hearing all the pain and ecstasy,” he remarks.

The last thing Smith wants to do is turn a deaf ear to misery. “If there are people who feel angry and hostile, we’ll dialogue with them ‘til Hell freezes over,” he says emphatically. He wants to be there to listen, if for no other reason than to show someone that hope can exist in what may appear to be a hopeless situation.

“Life is out there on the delicate edge,” he says. The delicate edge, where the seams that hold a community together are frayed and untidy. Smith uses the analogy of a tree when seeking to explain why he looks at the fringes of society to help heal it as a whole.

What happens when you cut a tree straight across its trunk, he asks. It grows back. What happens whenyou cut a ring around the trunk? It dies.

And what is a society without a spirit? “A stinking dead society,” Smith says. He is half-joking, but this is his cause, the quest to rekindle spirit in a lifeless society.

The reason Smith is out there every day, conversing with people, listening to them, is because he can’t stand to see their passion for life evaporate. And he’s going to try his damndest to see that they get it back, “Looking into the eyes of high schoolers, there’s no fire there. That breaks my heart. For God’s sake let’s get this bus on the road again!”