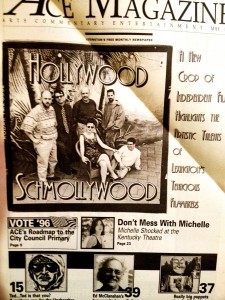

Ace coverstory May 1996

Everyone in this business longs to be able to tell somebody off; to walk out the door, slam it behind them, and swear never to do business with ‘those assholes’ again. But the only way you can do this is if your mouth, throat, and stomach can swallow and digest feathers, beaks, and gnarly, wrinkled claws. Because sooner or later, you’ll find yourself in a situation where ‘those assholes’ are the only ones who can help you get your film made. And then what you have to do is eat every single bit of that nasty, dead crow you flung so joyously in their faces.

Everyone in this business longs to be able to tell somebody off; to walk out the door, slam it behind them, and swear never to do business with ‘those assholes’ again. But the only way you can do this is if your mouth, throat, and stomach can swallow and digest feathers, beaks, and gnarly, wrinkled claws. Because sooner or later, you’ll find yourself in a situation where ‘those assholes’ are the only ones who can help you get your film made. And then what you have to do is eat every single bit of that nasty, dead crow you flung so joyously in their faces.

— independent filmmaker, Tom DiCillo (Living in Oblivion)

Hollywood doesn’t exactly intersect with Vine in Lexington. (It actually connects Sunset Drive and the South Ashland extension.) And while Lexington might not be the last place most people would look for a thriving film industry, it would probably be in the bottom five.

That’s a perception several Lexington filmmakers are striving to dispel. With nearby supporters such as KET and Appalshop (in Whitesburg), documentaries relevant to the region have long been popular. Tackling topics ranging from supporting a family on minimum wage to the toll the coal industry takes on land and people to the many profiles of Kentucky artists (such as the late AIDS activist and writer Belinda Mason). Feature films have also been well received, such as Paul Wagner’s production of Ed McClanahan’s story A Congress of Wonders.

Judging from the prevalence of local premieres over the past few years, it’s clear that there’s no shortage of interesting subject matter, and no shortage of filmmakers with the artistic vision and perseverance (average projects take three to five years) to see the project through.

Current projects in various states of completion include a gritty feature film on murder and mayhem, 100 Proof; a slick documentary on the Kentucky Derby (You Ain’t Seen Nothin’); a project focusing on the relationships between mothers and daughters in a small town (Mother Love) and a documentary about a recently deceased cowboy actor, Ben Johnson (Third Cowboy on the Right).

100 proof

With audiences that have been receptive to such somber style and topics as those featured in Kids, Dead Man Walking, Leaving Last Vegas, and Fargo, producer George Maranville and director Jeremy Horton are hoping that the climate is right for their soon-to-be-released independent feature, 100 Proof.

It’s horrible to insult the intelligence of audiences with tag lines, like “If you liked Blood Simple, you’ll love 100 Proof,” but for the purposes of supplying a hook to hang your perspective on, suffice it to say that Thelma and Louise might have looked a little bit like 100 Proof if Hollywood had been a little more willing to let the characters be as resolutely trashy as they were written–if they hadn’t had to look so much like Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis road-tripping their way to a wicked tan and redemption.

Lexington natives will immediately recognize the parallels between the movie and the late 80s murder spree case involving LaFonda Fay Foster and Tina Hickey Powell. But the film is more of an “inspired by” rather than “based on” situation. The similarities begin and end with two female characters who go on a crime spree, killing three men and two women.

A preliminary cut of the film was recently screened at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, prompting reactions Maranville described as “disturbed” and “upset.” One woman, in criticizing the film, compared it to In Cold Blood, and Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer. Maranville found it difficult to take her comments negatively since he was actually “honored” to have 100 Proof mentioned in the same context as those films.

It’s easy to see why one audience member described the film as “too real.” Pat McNeese’s art direction and production design has populated the scenes and sets with a depressingly vivid array of aging linoleum, fraying upholstery, decaying sedans, and (in an all too masterful stroke of verite) enough Ale 8 1 to choke a horse. When press, McNeese will reluctantly acknowledge being “in touch with that jeeter aesthetic,” not entirely convinced that “jeeter” hasn’t been banished from the lexicon by political correctness proponents.

One film Horton didn’t want to make was Kalifornia, a movie he “hated for its trailer park stereotypes.” Instead he sought to tell a story about two women with “nothing to look forward to but walking from place to place…and there’s not much there when they arrive.” He says you can walk into any downtown bar “and find people much worse off than Rae and Carla. This is just an interpretation. The film diffuses reality.” It’s important to him that viewers not see it as “a freak show.”

Horton is interested in seeing southern film develop a niche for itself the way southern fiction has. It seemed the industry was off to a good start with such early efforts as Night of the Hunter (1955), Cape Fear (1962), Cool Hand Luke (1967), and even the controversial Deliverance (1972).

Recent years, however, have generally seen southerners reduced to squawking stereotypes with such homogenized, anesthetized fare as Steel Magnolias and Crimes of the Heart.

Five years in the making, 100 Proof has managed to capture the aimless existence and barely-beneath-the-surface despair of its characters, without resorting to embarrassing caricature. Even a blessedly restrained Jim Varney manages to show off his classical roots (and briefly shed his Ernes stigma) in a brief but effective cameo as Rae’s alcoholic, abusive father.

A major coup for the film was scoring famed southern author Larry Brown for the role of a drug-dealing country store owner. Horton came by Brown’s acting services via a Nashville book signing, where he stood in line to ask Brown’s permission to send him a copy of the script. The author came on board almost immediately. Among his first comments on the script was, “these girls sure do say ‘fuck’ a lot.”

He’s right. They do. And saying much more abuot it would be giving away the store. The film is currently in post-production in preparation for a May distributors’ screening in New York. The next step will be to submit to Sundance and Berlin for 97.

Describing the process of making the film as very much like raising a baby, Horton says they’ve gotten the kid to his teenage years. Now they’ve just got to get him into college.

Next up for Horton is a documentary abuot the actor Jack Johnson, who plays Arco in 100 Proof. Maranville is developing two feature film scripts, one of which (he prays) will be shot this year. He’s also continuing pre production on Darker Days, for the PBS program ECU (Extreme Close Up, a spinoff of POV). There are, sadly, no plans to revive Maranville’s local access “seminal drunken alternative movie review show, Brains on Film,” with Larry Joe Treadway.

At press, 100 Proof is shopping for a distributor.

YOU AIN’T SEE NOTHIN

Many filmgoers were introduced to director Louis Guida with Saturday Night, Sunday Morning: the Travels of Gatemouth Moore. The story of a gifted blues singer who gave up showbiz to become a minister, the production won an American Film Festival Bleu Ribbon. Guida also won the CINE Golden Eagle for When You Make a Good Crop: Italians in the Mississippi River Delta.

The title of Guida’s current production You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ has its origins in the famous Irwin Cobb quote: “Until you go to Kentucky and with your own eyes behold the Derby, you ain’t never been nowheres and you ain’t seen nothin.'” The production certainly does nothing to dispel that myth. With its slick look (thanks to Academy-Award-Winning cinemetographer Nick Doob), this piece is fully equal to its subject matter in style and glamour.

The Derby is described by Guida as “an aspect of American culture,” and the film explores it as such. Featuring perspectives from all walks of life — from owners to trainers, from millionaires to infield revelers to the lady who slices the world-famous Derby pies — everyone has an opinion about what many describe as the greatest two minutes in sports.

The film opens with a jazzy rendition of the call to the post. The next thing you hear is a fan saying, “Somewhere between maternity and eternity, everyone should come to the Kentucky Derby at least once.” He’s wearing a replica of Churchill Downs on his head.

Joe Durso of the New York Times says the Derby’s success is at least partially due to the sentimentality of the event. “People will pay for that experience.”

Leslie Sanders probably wouldn’t argue with that. For the past ten years, she’s been cutting Derby pies. She loves the event for the annual wardrobe parade. She smiles wide for the camera, “I just love fashion.”

Pat Valenzuela weighs in on what an expensive proposition racing is. He saiys of Arazi, “the European super horse” of the 1992 Derby, “if he doesn’t win, maybe he’ll have to swim home.”

The film’s most amusing moment comes during the interview with the Pentecostal church members who are selling souvenirs across the street from Churchill Downs. When asked how they reconcile their anti-gambling beliefs with the Derby spectacle, one vendor says, “we don’t gamble…we don’t judge.” The woman standing next to him further justifies the paradox with “the devil’s gettin’ his share.”

As William Faulkner wrote in his 1995 Sports Illustrated essay on the Derby, “This may be the way we will assimilate and endure it: the voices, the talk, at the airports and stations from which we scatter back where our old lives wait for us, in the aircraft and trains and buses carrying us back toward the old comfortable familiar routine like the old comfortable hat or coat; porter, bus driver, pretty stenographer who has saved for a year, scanted Christmas probably, to be able to say, “I saw the Derby.”

Fan Ernie Kroviak tells the filmmakers “a bad day at the track is better than a good day anywhere else.” But the last word goes to the woman who said, “if I were to come back for a weekend at the Derby…I would bring my needlepoint.” It’s all in how you look at it.

You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ premiered at the Kentucky Derby Museum on April 29, 1996. The video will be available for purchase at such outlets as the Derby Museum and the Keeneland Gift Shop.

MOTHER LOVE

Just in time for Mother’s Day comes the latest Cafe Sisters documentary, Mother Love.

The Cafe Sisters, Eren McGinnis and Christine Fugate, are probably best known locally for their production, The Southern Sex, a film that explored the lives of southern women.

Eren McGinnis describes the process of independent filmmaking as being a “50/50 split between fundraising and movie making.” Fugate says “independent filmmaking is difficult at best.”

McGinnis, discussing her current distribution efforts with libraries says, “distribution” has sometimes meant selling a copy of one of their videos to pay the copy bill at Kinkos.

Fugate currently works in the film industry in Los Angeles, where there are more opportunities than here — though she returns frequently to collaborate with McGinnis. McGinnis also has family out West, facilitating the partnership logistics.

Pikeville mothers and daughters were chosen as the subject for this documentary because the filmmakers wanted small town dynamics “where mothers and daughters still live together.” They were also interested in Eastern Kentucky for the economic range present, ranging from poverty to wealth. McGinnis says they were fortunate to be invited into the homes and lives of their subjects, acknowledging that the filmmaking process was “very invasive.”

The film deals with universal issues between mothers and teenage daughters (like the definition of ‘overprotective’ vs ‘strict’) but also features winning segments on a mother and an adult daughter who’s returned to the area after a painful divorce (from a man her mother never liked anyway). The mother had told the daughter of her prospective divorced fiance, “I would never be anyone’s second choice.” The daughter, clearly hurt, responded “Well lucky for you. But that’s not how things turned out for me.”

Some of the daughters are typically obnoxious teenagers, some are more charming. Jamie, for example, clearly has great love and respect for her mother. The film also chronicles their move to a Habitat for Humanity house. Jamie’s mother shares some hard-earned wisdom with her, “When you marry a person, you’re not buying a horse or a slave. You don’t own that person. Don’t let a man do you that way.”

From the mouths of babes…one adolescent says, “I wanna marry a man that’ll work…not me have to do it all. I don’t wanna man that’ll lay around on the couch all day. And drink. And expect me to wait on him.”

The end of the production features a local radio show. The topic is mothers. One caller talks about how hard it is when your mom isn’t at the other end of the phone anymore. She offers some cautionary advice, “The time to pay tribute to them and love them is now.”

The next Cafe Sisters production may deal with the tobacco industry, focusing on how the farmers are diversifying and what that means. If the project goes through, it may be the biggest budget they’ve worked with so far. They might not even have to sell any videos to produce it.

THIRD COWBOY ON THE RIGHT

Adding a sad note to Third Cowboy on the Right was the April 8, 1996 death in Arizona of the documentary’s subject, Ben Johnson. The 76-year-old actor was known for his work in such John Ford films as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950). Younger film fans may best remember him for his Oscar winning portrayal of pool hall owner, Sam the Lion, in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971).

Ben Johnson: Third Cowboy on the Right is a work-in-progress by Fly-by-Noir films. Tom Thurman is the project’s director, producer and editor, and Tom Marksbury is the writer. Video Editing Services’ Arther Rouse shot the project, all of which was completed prior to Johnson’s death. Final editing is in progress. This isn’t Fly-By-Noir’s first foray into such subject matter; their Warren Oates project, Across the Border, was a thoughtful examination of the life of an actor probably most famous as a member of Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch.

Like all Fly-by-Noir efforts, the current project is beautifully scored by local musician Frank Schaap. His spare, lonely guitar work here does as much to conjure the American west as the cowboy actors themselves do. His efforts on this project are augmented by Warren Byrom on fiddle.

Ben Johnson is modest and self-deprecating in the film’s interviews. He says, “I’m not the greatest actor in town, but I can play the heck out of Ben Johnson…and I think people like Ben Johnson. If they didn’t, I wouldn’t have been around this long.”

Judging from the actors (like Harry Dean Stanton and Charlton Heston) who lined up to weigh in with praise of Johnson, he has the last part right. But they’d take issue with his assessment that he’s just playing Ben Johnson. His peers seem to think that was his greatest gift and grace as an actor — to make it seem so easy, to make it look like he was just playing Ben Johnson.

Charlton Heston describes Johnson as “the epitome of the Western man.” Appearing in such classics as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Wagonmaster, Rio Grande, and Hang ‘Em High, he and contemporary John Wayne are the most recognizable heroes of the genre.

Working within the dark and nihilistic vision of Sam Peckinpah, and the slightly more optimistic world of John Ford, Ben Johnson interpreted the American West as well as any cowboy before him, he just never got quite the recognition the Duke did.

Third Cowboy on the Right will have its world premiere at the International Film Festival in Munich, July 1996.

***

In a recent Vanity Fair issue devoted to the film industry, B-movie producer Roger Corman was quoted as saying, “anyone who can operate a lathe drill can direct a movie.”

After viewing selected projects from some of Lexington’s current crop of filmmakers, it’s obvious that Corman may be underestimating the craft a bit. Of course, this is the same man who instructed Martin Scorsese in the art of screenwriting, “Remember Marty, that you must have some nudity at least every 15 pages.”

In the face of such traditional Hollywood standards, these local projects may not measure up.

What could be more wholesome than Moms and Cowboys, for example? And the closest one of these films gets to nudity comes when a young lady in the infield exposes her breasts in Guida’s derby documentary. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on your perspective), her male companion thoughtfully censors her assets with his hands.

And if it’s violence you want, even 100 Proof’s disturbing exploration of homicide and aimlessness is low on the gore factor. Most of the murders are implied, and even the gunfire is the more realistic (and cinematically unsatisfying) sound of a firecracker, as opposed to the cannon-like explosions you get in say, a Lethal Weapon. That may indeed be a little “too real” for some viewers, who like their mayhem a little more stylized.

So whatever’s next for those profiled here, the next stop probably won’t be Die Hardest, or even Ernest Needs a Kidney. And for that, we can be grateful We may reside firmly in an outpost of western civilization fondly known by many as Hooterville, but our cultural and artistic sensibilities remain uncompromised by these filmmakers.