[two_third]

Taking A Hardline For Hemp

Could this controversial crop be the key to Kentucky’s agricultural future?

By Campbell Wood

“I’m honored that the governor asked me to be a part of the task force to study hemp,” says Jake Graves, who, in addition to his place on the task force, is the president of the newly revived Kentucky Hemp Grower’s Cooperative Association, “but I’d rather people think of me as a Kentucky farmer acting in the interest of the future of our farmers.”

He gazes though the windshield into the thick snowfall that has whitened the highway on this Tuesday evening in February. His son Andy, also a farmer and vice-president of the Fayette County Farm Bureau, is behind the steering wheel of the Chevy Blazer, hauling a horse trailer loaded with a 500-pound bale of raw hemp stalks. This bale represents the first legitimate hemp crop grown for agribusiness in North America in over thirty years. In the back seat is David Spalding, an agricultural economist who is an Extension Associate with the University of Kentucky Horticulture Department.

“Here I am,” Jake picks up, “a sixty-eight year old man, traveling through a blizzard at night to try and convince folks that hemp is a viable crop for Kentucky. And some think we’re trying to put angel wings on the devil.” He shakes his head. “Just the fact that hemp makes a superior paper to wood pulp, and that it keeps the environment cleaner, should be enough for anyone.”

But there’s much more to tell, and on this night, the group is on its way to share the message with farmers in Lebanon, Kentucky.

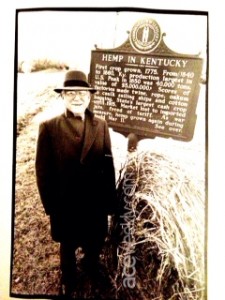

Jake Graves is an unlikely representative for what is widely regarded as an outlaw crop. Graves is a well-respected businessman in Kentucky-his family has been in banking since 1865. Since 1948, Jake himself has been a leading banker in the Bluegrass, and retired in 1993 as Chairman of the Board and Director of Commerce National Bank. He is currently Chairman, Honorary Emeritus, of National City Bank of Lexington. Since 1942 , he has owned and operated Leafland Farm, 1200 acres devoted to grazing cattle and to growing a few crops, including tobacco and grains. His list of civic involvements is lengthy.

The point is, he’s not the kind to be written-off as an on-the-fringe rabble rouser.

The Graves family began farming this region in 1810. From the start, hemp was a mainstay crop, as it was with most Kentucky farms. The Kentucky hemp fiber was very much tied to the cotton industry; coarse cloth and twine made from Kentucky hemp was used for cotton bailing. The seed, high in nutrition, was excellent bird feed. The plant’s fiber ws used extensively in fabrics for clothing, canvas, and primarily ship riggings.

The early 1900s brought steam ships and a declining market for hemp fiber. It also brought the marijuana scare, which vilified the plant without distinguishing the psycho-active variety from the commonly grown fiber crops that were virtually useless as hallucinogenics. In 1937, the Marijuana Tax Act put a damper on hemp as an American agricultural crop, which was already on the decline due to changing marker conditions.

“In 1941,” says Graves, “with the rumblings of war crossing the oceans, my father moved to corner the market in hemp seed. He went up and down the river buying up the seed from farmers.” Historically, war has always brought a boom to the hemp market. With the possibility of fiber markets in the Philippines being cutoff by the Japanese, Grave’s father saw the need for domestic hemp. Unfortunately the Army, under the War Powers Act, took possession of Graves’ hemp seed, along with one of his farms and a tobacco warehouse.

A fiber hemp crop is easily to distinguished from a drug crop. Fiber hemp is grown in very tight rows, each plant about four inches from the other. The crop is grown for the stalk and produces few leaves. Drug crops are grown for the leaves, so the plants, growing full and bushy, are spaced much wider.

It was that year that Kentucky Hemp Growers Cooperative Association was established to help redistribute the seed and offer guidance and support to farmers. Also that year, Graves planted a hemp fiber crop for the war effort. Many other farmers planted hemp seed crops, banking on what could be a very lengthy war. An estimated 31,000 acres of hemp were cultivated, much of it in Kentucky.

“My father died before that first crop was ready,” says Graves, “so I was in charge of the harvest. It was regarded as such a high priority that Army personnel and German prisoners of war helped with the work. When the war ended, the crop fell off rapidly.” The last legitimate hemp crop in the U.S. was grown in 1957 in Minnesota. Although federal legislation exempted hemp from the marijuana law when it was grown for fiber or other products of the mature stalk or oil or cake from the seeds, farmers still felt uncomfortable growing a stigmatized crop. That discomfort, along with changing markets and the burgeoning petrochemical industry, brought an end to legitimate hemp farming in the U.S.

On the outskirts of Lebanon, the Blazer pulls up in front of a one-story brick building with a large sign over the door: Marion County Coon Hunters’ Association. Ten pick-up trucks and several cars are parked in the gravel lot. People arrive as the snow, still falling, accumulates.

About 25 farmers have arrived when the meeting begins with the showing of two videos on the viability of hemp and emerging markets. Hemp for Victory was made in 1941 by the Department of Defense to educate farmers about hemp. The Billion Dollar Crop/The Renaissance of Hemp, a documentary by Australian filmmaker Barbara Chabocky, documents world-wide markets for hemp.

One segment shows fields of hemp fiber crops in Holland, where the government has spent $15 million in hemp research. There, paper production with hemp fiber is underway. Another segment shows an Oregon lumber mill owner who is disconcerted with the leveling of millions of acres of trees annually, much of that wood harvested for fiber.. “If we bring on hemp as a fiber crop,” he says, “and start growing it in the massive quantities that we need it, then the price will drop and farmers will be able to sell it to the mills at a price that wil be cheaper than wood. Just give it a couple of years, and the price will be cheaper. It’s a hundred-and-twenty day crop as opposed to several hundred years. There’s no comparison.”

The following segment shows the Wood Products Division of Washington State University and the particle board they made with hemp fiber. WSU demonstrated that it can be done with the technology already in place for wood fiber.

Andy Graves rises from his seat. He goes to the bale of hemp and breaks off a piece of stalk. “This bale was sent down to us from Joe Strobbel in Ontario, Canada: the first harvested crop of industrial hemp in North America in quite a while.” He strips away some of the strands of the outer sheath of the stalk. “This is what the fiber comes from. And inside here, the woody core of it is called the hurd – it’s the cellulose, which can be used for pulp, paper, plastics, foods and a myriad of other products.”

“The French have been growing industrial hemp for over 20 years,” UK’s Spalding adds. “The British are now growing it. Over there, they’ve managed to regulate the growing of these crops without complications to their drug enforcement policies. To say that we can’t produce a crop and insure that it is only industrial grade hemp is a slap in the face of the American farmer-that’s like saying we’re not as smart or sophisticated as the European farmer.”

“We could do a compliance program very similar to what they have in Europe,” he continues, “and it would not be a whole lot different from how our tobacco farming is manages.” The farmer would get a license to grow hemp, and the fields for cultivation would be designated on an official map. A quota would be established; an official would observe the crop, and random clippings would be taken for analysis. A major difference from tobacco farming would be the use of only certified seed.”

According to Spading, fiber hemp would be an easy undertaking for farmers. Standard equipment on most farms will do the job, and it requires about the same amount of fertilizers as corn. Hemp requires no herbicide or insecticide. It grows fast, smothering weeds, so it’s useful as a rotation crop to keep fields clear.

“This fiber hemp would also bring some rural economic development,” says Spalding. “Because of the crop’s bulky nature, processing needs to be done in a 30-40 mile radius. Processing and other value-adding industries would bring more jobs.”

The cooperative’s role in this would be that of a brokerage house, setting up contracts for the growers with buyers. The co-op would also handle the distribution of certified seed. There are 18 registered varieties of hemp seed in Europe. The European standard for THC content in the crop is set at 0.3 percent. Drug crops typically range from 18 to 30 percent THC.

Additionally, a fiber hemp crop is easily to distinguished from a drug crop. Fiber hemp is grown in very tight rows, each plant about four inches from the other. The crop is grown for the stalk and produces few leaves. Drug crops are grown for the leaves, so the plants, growing full and bushy, are spaced much wider.

Jake Graves believes the only way industrial hemp will return to Kentucky is if farmers demand it. British farmers demanded it of their government, and they got it. “There are two things you can do,” he says. “Tell your governor you appreciate him sticking his neck out. The second: tell your representative to wake up!”

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Update:

The Governor’s

Hemp Task Force

By Campbell Wood

Governor Brereton Jones has gotten nationwide attention for his bold initiative in forming a task force to study the viability of hemp as a crop for Kentucky farmers. The 18-member task force includes leading farmers, state agriculture officials, heads of the agriculture programs at five Kentucky universities, and the Commissioner of the Kentucky State Police. The task force is to present the governor with its findings by the end of October.

“We are studying markets for legitimate hemp products,” says Gayle Glenn, task force member and head of the marketing committee. “I’ve divided the markets into four areas and assigned members to study them.” The market areas represented by the plant parts involved: see products for oils and seed cake; fiber products for textiles; inner hurd or cellulose for paper and biodegradable plastics; and a combination of fiber and hurd for building materials.

“We are studying markets for legitimate hemp products,” says Gayle Glenn, task force member and head of the marketing committee. “I’ve divided the markets into four areas and assigned members to study them.” The market areas represented by the plant parts involved: see products for oils and seed cake; fiber products for textiles; inner hurd or cellulose for paper and biodegradable plastics; and a combination of fiber and hurd for building materials.

“In my personal view,” says Glenn, “any farmer who wants to grow this non-drug hemp should simply be allowed to do so within appropriate controls. When the raw material becomes available, industry will being to form around it. And it could create cabin industries. One group of farmers I’ve spoken to would like to grow a fiber crop and make their own rope and twine for bailing and so on.” She pauses. “I’m also saying this as a farmer who’d love to have a new cash crop.”

Jim Claycomb, the governor’s agricultural liaison and a hemp task force member, emphasizes that the crop is not being looked at as an alternative to tobacco, but as a supplemental cash crop. He says that there are legal hurdles to get past in order to do any planting. “The state police and the attorney general’s office have reached some agreement on test plots for research. Of course, any planting would be done at controlled sites, such as the University of Kentucky. But before we do anything we need to have full approval at the federal level, which would involve the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Drug Enforcement Agency, and maybe the Justice Department, too.

“For the most part we’ve had a positive reaction to the task force,” says Claycomb. “There are some who think this is an underhanded way of getting to legalize marijuana. The governor is unalterably opposed to legalization of marijuana,”

[/one_third_last]

This cover story appears on pages 10 and 11 of the March 1995 print edition of Ace. Click to read pages 12 and 13.