“With her sincere honesty, her commitment to service leadership, and her intense passion for everything that she is involved with, Ashley Judd presents a multilayered portrait of how one person—committed, caring, and conscientious—can truly make a difference. She may be our program’s No. 1 fan, but after reading this, you can count me as one of her top fans.”

— John Calipari, UK head basketball coach

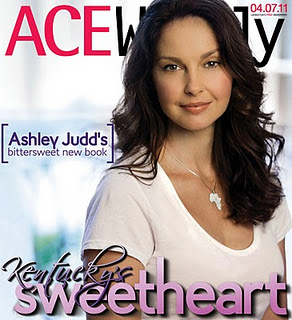

Ashley Judd knows how to school a heckler. One posted on twitter prior to the Final Four, “my only wish is to see ashley judd’s head explode if uconn wins. @ashleytjudd JORTS that, BITCH!” Her quick response called him out, “Mike, Your language is unnecessary and not appreciated.” Her profile identifies her as “Actor. Author. Activist. UK Fan.”

Her head didn’t explode with UK’s disappointing final four loss. She wrote, “Time to grieve tough loss and celebrate very special season.” That’s a consistent theme in her new memoir, released earlier this week, evident in the title, All That is Bitter and Sweet. In it, she chronicles her itinerant childhood (13 schools from the ages of 5 to 18), an occasional moment from her movie career (Ruby in Paradise; Bug; Come Early Morning) and in far greater detail, her avocation for the past seven years as global ambassador for international public health nonprofit, PSI (Population Services International).

Her head didn’t explode with UK’s disappointing final four loss. She wrote, “Time to grieve tough loss and celebrate very special season.” That’s a consistent theme in her new memoir, released earlier this week, evident in the title, All That is Bitter and Sweet. In it, she chronicles her itinerant childhood (13 schools from the ages of 5 to 18), an occasional moment from her movie career (Ruby in Paradise; Bug; Come Early Morning) and in far greater detail, her avocation for the past seven years as global ambassador for international public health nonprofit, PSI (Population Services International).

Anyone coming to the book expecting juicy Hollywood gossip will find none, beyond an occasional mention of a Golden Globe red carpet or an appearance at a Vanity Fair Oscar party (which led to her friendship with Bobby Shriver who—along with Bono—ultimately convinced her to serve as global ambassador for YouthAIDS).

Anyone expecting her to dish dirt on The Judds will be just as disappointed. While she doesn’t gloss over her painful childhood—with episodes of depression, which she called “spells” beginning around age 7— there are no searing Mommie Dearest details. The narrative is fairly straightforward—“this happened and this happened, then that”—there is almost no dialogue from her peripatetic youth spent shuffling back and forth between California and Kentucky and Tennessee. The early chapters are more geneaology than revelation.

In a moment that offers a quick glimpse into the sense of humor (not to mention gift for understatement) her friends say she’s famous for, Judd summarizes her mother’s lifetime of telling (and selling) a family narrative inconsistent with the facts with the statement, “My mother is a highly imaginative person who has always enjoyed a yarn.”

She writes, “eastern Kentucky still calls to me. Kentuckians have a deeply ingrained, almost mystical sense of place—a sense of belonging that defines us.” But she also points out that the mythology of “The Judds,” was often inconsistent with reality (beyond just the fact that she and famous sister Wynnona turned out to have different fathers, a former family secret exposed long ago). She writes of her Great Aunt Pauline’s beloved farm in rural Kentucky, which had an outhouse and a well, “It is this home that the press has often conflated with my other homes, writing that I grew up dirt poor without electricity and plumbing.” She didn’t, although there were elements to her life that did seem straight out of a country song (and ended up in more than a few).

Not surprisingly, on the day the book was released, the media seized on her morning interview with the Today Show, where Meredith Vieira characterized the memoir as a chronicle of Judd’s surviving incest. In reality, Judd devotes less than a page to it (an incident with the husband of a relative in her early adolescence), though she does spend significant chapters outlining her recovery from lifelong bouts of depression, including a 42-day stay at the same facility where her sister Wynonna was receiving treatment. In interviews (though she describes herself as mostly “abstinent” where the press is concerned), she describes the book as “honest,” moreso than “accurate,” acknowledging that individuals tell their truths as they see the truth.

Beyond feeling left out of her mother and sister’s life (often physically and literally), she was a sensitive child, and recalls being devastated when an early report card charged, “talks too much,” and an episode where her family made fun of her singing along with the radio, which she says, “broke my spirit.” She writes, “I never sang again. It was several years before my mother and sister began to sing together, but it was clear from the outset that I was not going to be included.” Kentucky grandparents provided a lone note of anchoring stability and she writes, “I spent every summer of my otherwise chaotic childhood with our grandparents in Ashland, and I believe they are the reason I am alive today.”

She writes glowingly of her time at the University of Kentucky where she was “ready to become a full-fledged social activist.” She worked shifts at WRFL, organized demonstrations against UK’s financial association with apartheid, and she helped lead a student walkout to protest Happy Chandler’s infamous use of the n-word. Post-college, she considered a stint in the Peace Corps before ultimately focusing on acting—postponing the life of service she felt destined to lead, until she ultimately integrated both in her 30s, maintaining acting as a “day job,” while “pursuing social justice and human rights at home and abroad.”

This time last year, she earned a midcareer Master’s from Harvard’s Kennedy School, which she discerned must be in need of “a Sicilian hillbilly rabble rousing actor activist,” though she was initially taken aback by a friend’s suggestion “why aren’t you going to Harvard?” blurting out in response, “why am I not putting a rocket up my ass and flying to the moon?”

She characterizes her plan to pursue graduate studies as “not so much a professional credential, but a passion credential.”

In August of 2010, she posted on ashleyjudd.com from the Congo, “Quite literally dripping with electronics, I walk through Dulles airport to my gate. I am holding my iPad, downloading books from Kindle to have to read while on my journey. So far, I’ve chosen Kentuckian Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle; she came to mind, of course, because her spectacular book, Poisonwood Bible, is set in Zaire (now DRC). I’ve been meaning to read this one, and the amazing Blackberry Farm, over in east TN in the Great Smokey Mountain National Park, was featuring it in their gift shop. It felt like a good fit, a distracting, companionable counter point to the aim of my trip.”

On her site, she writes about everything from Soweto to mountaintop removal (she has been a vocal opponent). A few months ago, she recorded the narration for the documentary, Kentucky: An American Story (airing on KET in May). Filmmaker Daniel Blake Smith says, “She clearly cares very deeply about Kentucky’s past; she was the consummate professional in doing the narration, offering astute suggestions here and there to make it stronger. As we worked through the recording down at Wildhorse Studio in Franklin, TN, Ashley told me about her new book and how she was agonizing over every word in it, just as she was with our narration.”

In the book, her most vivid descriptions are far removed from Hollywood and reserved for the astonishing poverty and misogyny that she encounters on her globetrotting trips as an advocate and activist. She describes escaping to the rooftop of a brothel in Kamathipura to get a breath of air, where she “found about ten children and a woman washing her dishes while rotten food floated in a growing puddle. They were dusty, filthy, but playful and animated by having a foreigner visit.”

It is this hands-on activism that occupies the majority of the book, as she’s clearly adopted an advocacy and service stance similar to that of Kentucky native George Clooney—if the cameras are going to follow celebrities anyway, why not aim them somewhere they can do some good, like Africa?

Throughout, though she’s able to immerse herself in the squalor and subjugation she finds, with the hopes of ameliorating it, she’s not naive about her role, and the fact that all of her journeys still lead her home to a very different life. She writes after encountering a starving toddler outside a clinic in Kinshasa, “before I knew it, I would be easing back into my velvety world of abundance and first-class problems. I would be barefoot in my office—the back porch—wearing a white nightgown, looking at fireflies, eating black raspberry chocolate-chip ice cream with Dario, surrounded by our well-fed, inoculated pets, while Astrid and all the friends I made on this trip will still be…here.”

But, she concludes, “my faith, my hope, and my core belief that we can change the world and manifest peace is ever renewed.”

Friday April 8, Ashley Judd will host the season finale of ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ the geneaology series on NBC. She recorded the narration for KENTUCKY—AN AMERICAN STORY, which premieres on KET May 24. She will star in the ABC series ‘Missing,’ later this year. Her next movie with Morgan Freeman, ‘Dolphin Tale,’ is scheduled for September release. (The TV series, The Judds, premieres this weekend on the Oprah network.)

[amazon asin=0345523628&template=iframe image&chan=default]