View PDF Ace coverstory. James Baker Hall Memorial issue. 7.01.2009

In Memory

In Memory

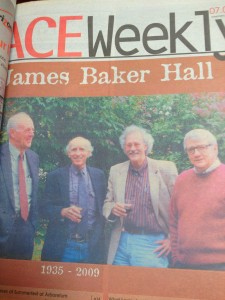

James Baker Hall 1935 – 2009

When James Baker Hall died last week he left behind a beloved family (wife and fellow author Mary Ann Taylor Hall, three sons) and a literary legacy as a UK Graduate, a Stegner Fellow, Kentucky’s former Poet Laureate, and a 30-year tenure as director of the writing program at the University of Kentucky. He was well-known for his writing, his photography, and his teaching. In these pages, friends and colleagues and former students share their memories of Jim. There will be a memorial service on July 11, 2009 in Gratz Park at 4pm (indoors at Carnegie Center if it rains). Reception follows at 5 pm.

The Elastic Trapezoid Minus One

by Ed McClanahan

Wendell Berry, Gurney Norman, James Baker Hall, and I — fledgling writers all — became cohorts and close friends when we were students in the UK

English department in the second half of the 1950s. (Bobbie Ann Mason

arrived at UK just as I was leaving, and we didn’t meet till many years later.) Between 1958 and 1962, all four of us snagged Wallace Stegner Fellowships in Creative Writing at Stanford University, and during those years and many more to follow, although we lived, variously, in California, Oregon, Seattle, Europe, New York, Kentucky, and Connecticut, we steadfastly maintained our four-cornered friendship—an “elastic trapezoid,” Wendell cleverly labeled it — no matter where, individually, we happened to find ourselves.

Eventually, of course, we all “found ourselves” — figuratively as well as literally — right back in Kentucky where we started; the trapezoid had finally stabilized, and squared its corners. Over the ensuing years, as will inevitably happen within long, loving friendships, the strength of our brotherhood would sometimes be tested in ways that had nothing to do with geography. But the bonds between us and among us always held; our tight little four-member fraternity endured, and ultimately prevailed, every time it was tried.

And then, alas, there were three.

Jim Hall was a consummate artist. His aesthetic, both as a writer and as a photographer, was demanding and exacting; he was, in the best and truest sense of the word, a perfectionist, yet his work was sometimes fearlessly

experimental, sometimes downright playful, but always adventurous,

always testing the limits, pushing the line back. He could stand the language

of poetry on its ear, and make his camera show you things you’d

never even dreamed of. In the prose he was writing early in his career—

I think particularly of his endearing first novel Yates Paul, His Grand

Flights, His Tootings (available at last in a new edition at fine booksellers

everywhere!), and also of a hilarious late-1960s short semi-fictional

memoir called “In My Shoes”—he was better than the young Woody

Allen at spinning pure gold out of personal free-floating anxiety.

Above all, though, Jim was a gentle soul, a sweet, tender-hearted

man, a delightful companion, and a luminous blessing in my life

for more than half a century. I will miss him always.

A Hundred Visions and Revisions: James Baker Hall – Friend and Teacher

by Guy Mendes

James Baker Hall was a homebred. He was a quintessential

local product, born and raised in Lexington,

Kentucky. Sure, he went off to the left coast and then right

— Stanford for grad school and Connecticut to live and teach

at UConn and M.I.T., but it was right here that he came of

age, that he learned to bleed Blue. Maybe it was his teenage

stint in the darkroom of the Mac Hughes Studio, which had

the UK Athletics Department account. If you were lucky

enough to have gone to a Cliff Hagan steakhouse with Jim,

he would proudly point to big prints of the former Wildcat

All-American and say, “I made those pictures when I was a

kid.” So eager was he to become a photographer that he

saved up and bought a book called Childrens Photography,

only find it was a book about taking pictures of children, not

how children could make photographs. And while he

learned photography working with a commercial outfit, his

later friendship with Ralph Eugene Meatyard would lead

him down a different road, one where photographs functioned

more like poems and talismans, more personal visions

than renditions of the real world. Of course, writing was the

other great passion of his life, and he found that calling at UK

in creative writing classes with Hollis Summers and Bob

Hazel (where he met kindred souls Berry, McClanahan,

Norman and Mason). Jim claimed that he never read a book

in high school. He had been a serious baseball player as a

Henry Clay High School Blue Devil and was an athletic-kindof-

guy all his life, but his jock days were numbered when he

encountered a piece of literature that forever changed his life:

T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

Jim was a triple threat — an artist, writer and teacher,

and he was a master of all three disciplines and was always

pushing their respective envelopes. Even though rooted in

real world imagery, his pictures were often other-worldly

and intensely introspective. His poems can be funny and

candid, or serious and provocative, and they are always told

in a distinctive, intense voice. As a teacher, he exemplified

what he used to say about a good photographic portrait —

that it is given as well as taken. Jim’s teaching was give and

take. He was quick to give of himself, and he greatly enjoyed

what he in turn received from his students. He opened his

own life up for us, and we did the same in response.

I met Jim through Ed McClanahan and Wendell and

Tanya Berry. I was on the staff of the underground newspaper,

blue-tail fly in Lexington in 1969, and we published

Jim’s words-and-pictures piece on Ed’s mythic alter-ego

Cap’n Kentucky. Two years later, when I was casting about

after college, Jim took me in as an apprentice in a small photographic

business based in a former veterinary hospital in

South Windsor, Connecticut. It was called The Dogrun

Darkroom. There wasn’t any pay involved, but I was given

room and board and film, chemicals and paper to use. It

was a great learning experience for me. Thirty-eight years

later and I’m still using the things I learned living with and

working with Jim.

Someday there should be a statue in Lexington of Jim,

hands in the air, talking, reciting, conjuring up the muse for

generations to come. His influence will long be felt in these

parts and beyond.

Some Random Memories of My Friend Jim Hall

by Guy Mendes

I have two photos of Jim in my study at home. One is titled

“James Baker Hall, Self-Portrait in Glass,” from 1982, where

he’s pointing his camera at himself and us simultaneously

and laughing at, I’d guess, the outright fun of the photo concept.

This shot fronted the announcement of Jim’s photo exhibition of

central Kentucky writers opening at the Ann Tower Gallery in

2002. I love the photo because it shows off Jim’s artistry and features

his contagious smile at a productive, healthy and important

time in his life — his second year as the state’s poet laureate.

The other photo is of my wife, Linda, lovely and tan in

her short summer haircut, Jim, and me. Linda and I are looking

directly at the camera. Jim, between us, is glancing up at

me, his white, bushy eyebrows slightly flared, and he’s saying

something.This shot was taken at the 2002

Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana Writers Roundtable at Hanover

College. As a former director of the yearly conference and a

friend of Jim’s, I was asked to introduce him that year when

he was the keynote speaker. For some reason, in the photo I

look huge; Jim looks smaller than he actually was. Maybe

this was simply the effect he had on people: when you talked

with Jim, he made you feel taller, better.

When I moved from Penn State to Lexington in 1986, I was

eager to meet and get to know other poets. I had heard of Jim,

of course, maybe even shared some pages in a couple literary

magazines with him. And somehow I knew what he looked

like, so when I found myself standing next to him at Kinko’s

(now the Kennedy Book Store art department) one day, I said,

“You must be James Baker Hall.” “God, I hope so,” he said, “or

else I’ve just been impersonating myself all these years.”

Coincidentally, we were both having poetry manuscripts

copied. His, the wonderful collection titled Stopping on the

Edge to Wave, was destined for publication by Wesleyan

University Press the following year. This serendipitous meeting

led to some immediate poetry talk and an invitation from

Jim to have lunch soon. When we did meet at Alfalfa a week

or so later, I recall that everyone there knew him; people were

drawn to our table for a word or two with Jim. He was a people

magnet, a home boy totally in his element.

I recall, too, a fine evening at Jim and Mary Ann’s house in

1992. They’d invited Linda and me for a dinner party with

another couple, and the evening began on a sour note. Jim’s

Larkspur Press book, Fast-Signing Mute, had just been

reviewed that morning in the Herald-Leader, a very negative

review that took Jim to task for “trotting out to the public,” I

believe the phrase went, a collection of Kentucky-based poems

that were written years earlier. That the poems weren’t new

was, as I recall, the damning criticism. Never mind that they

were engaging, well-crafted, and just plain fun to follow down

the page. It was an odd and irrelevant review really, but it stung

all the same (ACE also reviewed the book—but very favorably—

calling it, in the headline, Fast-Signing Muse. Jim loved

the typo and wondered if he shouldn’t have titled it that.)

After this small, literary speed bump, the evening went

wonderfully. I can’t recall the conversation but can still feel

the room erupting in a rosy glow over dinner soon after the

red wine made its rounds. Jim and Mary Ann were always

terrific hosts, as many of you reading this know, and there

was never any shortage of conversation — or wine.

In 2001 when Jim asked if he could photograph me for his

series of Kentucky writers, I was flattered, and of course said yes.

I had never been to his Lexington studio and had never seen him

in action as a photographer, so I was also curious about both.

Jim saw me drive up on the chilly December morning

and met me at the door. In the corner by the long staircase

leading up to his studio, lay, inexplicably, the disassembled

body parts of a mannequin. Jim seemed as surprised as I was

to see the pile of parts, but said, “Wait a minute. We might

need some of these.” He scooped up a couple of arms, a

twisted leg (Why would anyone rip apart a mannequin, I

wondered), and the head (“Let’s just leave the torso — I don’t

think we can use that”), and we climbed the stairs.

In his studio, Jim rolled down the white, seamless backdrop

and started shooting. I was struck mostly by his amazing

agility. He’d sit cross-legged and click off two or three shots,

spring up onto a chair for a few more, jump down, stretch out

flat for the next shots. He was a gymnast wielding a camera.

“Just cross your arms and look straight ahead,” he said

then. “No, there’s something missing.” At which point, he

picked up the purloined mannequin forearm and hand,

strode over, and stuffed the arm down into my jeans pocket.

“That’s it!” he said, and clicked away. The result was a photo

of me in t-shirt and jeans, a goofy expression on my face, and

a bright white hand signaling for help from my left pocket.

This wasn’t the photo Jim chose for the exhibition.

Instead, he selected one of me, wearing nothing but my own

body parts, relaxing in an overstuffed chair. There the photo

hung, on the opening night of the exhibition. I was also

pleased to see that the writer suspended from the ceiling next

to me, in our own private area of wall space, was none other

than my friend Ed McClanahan, who looked to be somewhere

in his 30s. Suddenly Jim’s hand was on my shoulder.

“I know you like to hang around with Ed, so here you

two are,” he laughed. I asked him how old Ed was in this

one. “Mid-thirties,” I’d say, Jim answered, after some

thought. “Here, in this space, though, he gets to be a lot

younger than you for a while.”

And now Jim is gone. As much as I hate that, I know that

we’ll keep him with us in memories like the few I’ve shared

here. And I know he’s eager to continue the conversation with

us, which will happen every time we slide one of his books off

our shelves and open it. We were lucky — all of us — to have

a stellar artist and friend like Jim Hall walk among us. ■

—JW

In Jim’s Words

by Ann Neuser Lederer

These quotes from James Baker Hall were jotted by me

while he led a poetry workshop I was privileged to

attend at The Carnegie Center for Literacy and

Learning in the Spring of 2000. Although this sample inadequately

portrays the full extent of his wisdom, knowledge,

artistry, and kindness, perhaps it hints at the range of his

influence, and the depths of our loss.

“If you can identify your fears, you know a lot.”

“The sound of deep feeling in language is unmistakable.”

“Language performs a priestly function — unapologetically sacramental.”

“The language of a poem should sound as if it has been slept on.”

“Poetry is to give birth to an object by blessing it.”

“The sound of truth telling is undeniable.”‘ ■

Goodbye Dear Warrior

by Pam Sexton

These quotes from James Baker Hall were jotted by me

while he led a poetry workshop I was privileged to

attend at The Carnegie Center for Literacy and

Learning in the Spring of 2000. Although this sample inadequately

portrays the full extent of his wisdom, knowledge,

artistry, and kindness, perhaps it hints at the range of his

influence, and the depths of our loss.

“If you can identify your fears, you know a lot.”

“The sound of deep feeling in language is unmistakable.”

“Language performs a priestly function — unapologetically sacramental.”

“The language of a poem should sound as if it has been slept on.”

“Poetry is to give birth to an object by blessing it.”

“The sound of truth telling is undeniable.”‘ ■

From a Student

by John Wright

In the fall of 2000 I had the honor of sitting in “the circle” of

Jim Hall’s Autobiography class at UK. For those who never

shared this honor, it’s difficult to express the effect Jim had

on his students. To say that he changed our lives is too easy. To

say that his wisdom, advice, and nurturing forced us to change

our own lives hits closer to the mark, but still doesn’t get it right.

Inside Jim’s classroom was a safety zone, filled with

laughter, candor, tears, admiration, and sometimes heated

emotions. He refused to teach in the sterile classroom of the

Whitehall Building. Instead, he pulled a few strings and had

our class moved to the homey and comfortable Gaines

Center. Jim knew that writing, as it should be taught, had

nothing to do with chalkboards, desks, or projection screens.

Jim’s classroom was a creative space where any emotion,

fear, fantasy, or desire could be expressed without judgment

or incrimination. The only catch was that our writing,

and our responses, had to be honest.

Jim made us better writers by demanding this honesty,

freeing us from the burdens of academic pretension and selfcensoring.

To be part of Jim Hall’s class you had to “show

up” every week, and “showing up” meant far more than just

warming a seat. I lived for Jim Hall’s class that fall, and I recognized,

even then, that what I was coming to know through

my work with Jim was special. What happened behind those

closed doors in the Gaines Center remains one of the most

formative experiences of my life.

We began that semester as a handful of awkward, shy,

and (in my case) insecure students. We ended the semester as

a strong, confident collective.

The lasting lesson I will take from Jim Hall is that to be a

good writer you must first be a decent human being. He taught

that being a writer requires constant attention to your own life,

a willingness to engage the fleeting and unknowable, and the

humble acceptance that one lifetime will not be enough to get

it all right. Being a writer means you have to try anyway.

It’s difficult, now, to imagine the Bluegrass without Jim Hall

in it. His commitment to the state, to local bookstores and writers

groups, to everything that is strong and wise and worldly

about Kentucky, and, most importantly, his commitment to the

young writers he encountered along his way will be truly missed.

If those in Frankfort had any sense the courthouse flags

would have sailed at half-mast on the day Jim Hall died, for

he was one of the Bluegrass’ finest and we’re all a bit better

for having known him. ■

—John Heckman Wright; Portland, OR; Student, 2000

An Appreciation

by Todd Hunter Campbell

In the fall of 2000 I had the honor of sitting in “the circle” of

Jim Hall’s Autobiography class at UK. For those who never

shared this honor, it’s difficult to express the effect Jim had

on his students. To say that he changed our lives is too easy. To

say that his wisdom, advice, and nurturing forced us to change

our own lives hits closer to the mark, but still doesn’t get it right.

Inside Jim’s classroom was a safety zone, filled with

laughter, candor, tears, admiration, and sometimes heated

emotions. He refused to teach in the sterile classroom of the

Whitehall Building. Instead, he pulled a few strings and had

our class moved to the homey and comfortable Gaines

Center. Jim knew that writing, as it should be taught, had

nothing to do with chalkboards, desks, or projection screens.

Jim’s classroom was a creative space where any emotion,

fear, fantasy, or desire could be expressed without judgment

or incrimination. The only catch was that our writing,

and our responses, had to be honest.

Jim made us better writers by demanding this honesty,

freeing us from the burdens of academic pretension and selfcensoring.

To be part of Jim Hall’s class you had to “show

up” every week, and “showing up” meant far more than just

warming a seat. I lived for Jim Hall’s class that fall, and I recognized,

even then, that what I was coming to know through

my work with Jim was special. What happened behind those

closed doors in the Gaines Center remains one of the most

formative experiences of my life.

We began that semester as a handful of awkward, shy,

and (in my case) insecure students. We ended the semester as

a strong, confident collective.

The lasting lesson I will take from Jim Hall is that to be a

good writer you must first be a decent human being. He taught

that being a writer requires constant attention to your own life,

a willingness to engage the fleeting and unknowable, and the

humble acceptance that one lifetime will not be enough to get

it all right. Being a writer means you have to try anyway.

It’s difficult, now, to imagine the Bluegrass without Jim Hall

in it. His commitment to the state, to local bookstores and writers

groups, to everything that is strong and wise and worldly

about Kentucky, and, most importantly, his commitment to the

young writers he encountered along his way will be truly missed.

If those in Frankfort had any sense the courthouse flags

would have sailed at half-mast on the day Jim Hall died, for

he was one of the Bluegrass’ finest and we’re all a bit better

for having known him. ■

—John Heckman Wright; Portland, OR; Student, 2000

Todd Hunter Campbell currently teaches creative writing and composition at the University of Kentucky, where he was privileged to take workshop with James Baker Hall over many years.

A Memorial for James Baker Hall is scheduled for Saturday July 11th,2009 at Gratz Park (it will move indoors to The Carnegie Center if it rains). Service is at 4 pm; reception follows at 5 and will include an informal poetry reading for guests who would like to bring and share a poem.