BY ROB HULSMAN

The truth is stranger than fiction, that’s what Flannery O’Connor said, and it’s the truth, especially down here.

And the truth did get mighty strange and grisly on the night of April 23, 1986, “down here” in Lexington, Kentucky. LaFonda Fay Foster and Tina Powell went on what has become one of, if not the most notorious murder sprees in Lexington’s history. Shooting, stabbing, running over or burning five people in one night, fueled by cocaine and alcohol. Foster and Powell penned their place in history with blood. This sort of mayhem caused quite a stir in a town where basketball is considered serious news.

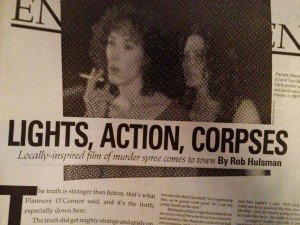

“Everybody was talking about making a movie, but nobody was doing it,” recalls Jeremy Horton, who wrote and directed 100 Proof, a film inspired by the murders. Deciding to do something about it, Horton and fellow Lexingtonian George Maranville teamed up and sold the indie project to Mammoth. Three hard years and several film festivals later, the duo are finally set for the local premiere of their work January 23rd at Lexington’s historic Kentucky Theatre.

100 proof is a schizophrenic movie that vacillates between the dark moodiness of Blue Velvet and the cheap aura of 10,000 maniacs.

Beginning with overtones of sexual abuse, the movie is a chunk of depressing, gritty reality. Even the look of the film is dark and claustrophobic, giving the viewer a creepy feeling from frame one. Pamela Holden Stewart, an Actor’s Theatre of Louisville veteran, plays Rae, the character inspired by Foster.

“I talked to Pam for about two minutes and realized the game was over,” Horton says. “When we started talking about the script and about what I was trying to do and what I really wanted to say, she was hitting it right on the head. [She was] actually kind of pissing me off about things she wanted to do for [the script], you know, bring it in and change some things and ‘make it better.’ And I was like “who the f are you to want to make this…’ you know, and that’s what I secretly wanted. Ten minutes into that [I decided], ‘You’re gonna be fine, we’re gonna work great.’ So I cast her pretty much on the spot.”

Moments of Rae’s rage that seethe from the stony-faced Stewart have true intensity and subtlety. Her character unravels as bad circumstance and substance abuse drive her closer to the brink.

These moments are unfortunately dulled by hamfisted explanations of past abuse, awash in movie-of-the-week sentiment. A very strong central cast in general though, propels the movie past these awkward spots. Stewart and Tara Bellando’s onscreen chemistry is particularly seamless. The supporting cast nevertheless are just the kind of cue-card reading fodder MST3000 fans crave.

“There’s a mix of real actors and non-actors in this thing,” explains Horton. “One of my big concerns is making people sound like they’re from here, so I wanted to bring as much of the local color, especially with the actors, or non-actors, as I could.” This “local color” unfortunately, occasionally derails the slow-burn build of intensity throughout the film.

Another strong presence in the film is Jack Stubblefield Johnson, who plays Arco, the seemingly near-death target of Rae’s outrage. This veteran of local stage and founding member of Actor’s Theatre of Louisville wheezes life into the pathetic old character. Horton had worked previously with the ailing Johnson. “I didn’t know he was in such poor health, when I met him [again], I said ‘Well, Jack, you really are Arco; you look like him, you walk like him.’ Jack isn’t really acting as much as he looks like he is — he really is in pain.

Lexington locales provide a perfect backdrop for this grisly tale of country and city colliding in Appalachia’s backyard. The local, sleazy underworld of cocaine is portrayed dead-on by a very greasy Jim Varney. His cameo as Rae’s father is a nasty reminder of the dregs of society existing outside of the light.

Unfortunately, the film merely brushes up against the underbelly of Lexington’s honky tonk underworld and bogs itself down in self indulgence before finally picking back up for its brutally stark end.

As for the post 100 Proof future, Horton has bought the rights to a Larry Brown story, “Roadside Resurrection.”

Horton and Maranville co-wrote an adaptation of the story, even though in Horton’s rare words, they “hate each other severely.” This strong and apparent tension between the two is something both parties speak of guardedly. Neither seems to be dwelling on the negative, though.

“I’m the most excited I’ve ever been,” gushes Horton. “You know I used to walk by the Kentucky Theatre and think wouldn’t it be nice to show your own movie. And I’m going to show the thing that we worked on forever — it’s been a long time. There’s been a lot of ups and downs; we’ve gone to Sundance and played New York; there’s been so many highs — come January 23, it’s going to be a nice day for me, that’s for sure.”