Ace September 1994

BY CAMBELL WOOD

Stored at the Blue Grass Army Depot in Richmond Kentucky are munitions that contain three types of chemical agents: H blister agent (mustard), GB nerve agent, and VS nerve agent. There are approximately 70,000 M-55 rockets containing GB and VX nerve agents. The rockets are obsolete, so the number of rockets held is no longer classified information. This is not true of the8-inch round Howitzer ammo loaded with VX agent or the 155 mm projectiles loaded with mustard; the quantities of these are classified because the firing mechanisms are still in use.

There is also a one-ton container partially filled with nerve agent buried in the ground.

Mustard gas as used in bombs is actually a kind of jelly. Whether in a more liquid form or vaporized, it is extremely toxic. Exposure can result in severe eye injury. It quickly passes through clothing, causing severe burning and blistering to the skin. Inhaled vapors can cause chronic long term respiratory disorders. It also causes systemic effects such as vomiting, prostration and death. Effects apear several hours after exposure.

Nerve gas enters the body either through inhalation or skin absorption. It inhibits the chemistry which controls muscular functions. The buildup of Acetylcholine throws the entire muscular system into uncontrolled spasms, affecting all bodily functions. The nose runs, the chest tightens and vision dims. Breathing becomes difficult. The victim experiences nausea and vomiting. Ultimately, convulsive spasms end in death.

History

Chemical weaponry effectively entered modern warfare in World War I when the German military attacked the Allied forces with chlorine gas. A few years later, Germans introduced cihloro-diethylsulphide, better known as mustard gas for its distinctive odor. Teh horror of chemical warfare prompted 38 nations to agree to no first use of chemical weapons when representative signed the Geneva Protocol in 1925. This didn’t hinder nations from continuing research and stockpiling massive reserves.

In the 1930s, the German military took notice when industrial insecticide research discovered three highly toxic compounds known as the G agents: Tabun (GA), Sarin (GB), and Soman (GD). These were the first nerve agents. They represented a ten-fold increase in toxicity over the old chemical weapons. The Germans refrained from using the nerve agents in World War II, however, at the end of the war, The Russians and the Americans captured the nerve gas technology and developed extensive arsenals of it. In the 1950s, British chemists discovered the even more deadly V agents. Unlike the G agents which were evaporative, the V agents stay around much longer — they can even be absorbed by vegetation. A tiny drop of V agent is lethal.

Beginning in 1962, U.S. and Soviet leaders began negotiating a ban on the weapons. This agreement was reached on January 13, 1993 when 138 countries signed the Chemical Weapons Convention. The 192-page treaty will ultimately result in the formation of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). The OPCW will monitor the destruction of the stockpiles. The U.S. is estimated to have 30,000 agent tons. Estimates for Russian stockpiles vary widely, from 40,000 to 700,000 tons.

The treaty requires the U.S. and Russia each to destroy all chemical weapons within ten years of the treaty’s enactment. The goal for ratification is 1995, establishing 2005 as the date for completion of destruction.

Incineration

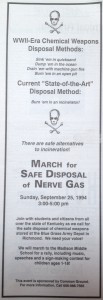

Disposing of chemical weapons is not new. According to the Bulletin for Atomic Scientists, at the end of World War II, the Allied Forces dumped over 300,000 tons of chemical munitions into the Scandinavian seas by loading them into patched up war ships and scuttling them.

Scandinavian fishermen continued to find globs of still active mustard gas jelly and deteriorating shells in their nets. Ocean dumping of chemical weapons continued until Congress passed the 1969 Oceans Dumping Act, prohibiting such waste disposal.

Incineration became the Army’s choice for disposing of the stockpiles. At the time, the decision didn’t generate opposition. Ocean dumpign was out; hazardous waste in landfills was contaminating ground water, and little was understood about incineration.

In a Greenpeace report, Playing with Fire — Hazardous Waste Incineration, Pat Costner and Joe Thornton document research findings that shed light on the dangers posed b the process: “Incinerator stack emissions carry waste chemicals that have escaped combustion as well as newly formed ‘rpoducts of incomplete combustion (PICs).”

PICs include dioxins, furans, PCBs and other complex molecules that are highly toxic and linked with disease states, and which accumulate in the environment. Studies conducted in various parts of the world showed that within close proximity to hazardous waste incinerators there are significantly increased levels of toxic compounds in mothers’ milk, cows’ milk, meat and eggs. Crops have also shown contamination. Added to these problems are the tons of toxic ash and brine, by-products of incineration, that must be landfilled.

The prototype incinerator for the Army’s Chemical Weapons Disposal Program has been in operation since 1990 on Johnston Island, about 800 miles southwest of Honoloulu. The Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) combines robotics with four different incinerators.

One critic of the Army’s program is Dr. Paul Connett, PhD, who has studied incineration closely for ten years. In a phone interview, he commented on the JACADS facility, “The average person doesn’t know what happened at Johnston Island. I was very shocked when I reviewed the data to see how many technical problems they’d had there. Nothing else that we burn is designed to kill people. To deal with this problem, you must make sure you have a technology that has a track record of successful operation. Incineration doesn’t have such a record.”

Pat Costner, toxics research expert with Greenpeace, describes the JACADS system as having “had an array of many, many problems, making it unable to meet performance standards. Trial burns conducted at the plant resulted in numerous releases of agent in worker corridors, and active agent was detected at the perimeter of the facility.”

Due to upset conditions in the process, JACADS had more downtime than operational time. “Even relatively short-term operation of incinerators in upset conditions can greatly increase the total incinerator-emitted loadings to the environment,” Costner wrote in the report.

The incidents at JACADS have not deterred the Army from constructing a second incinerator in Tooele, Utah, largely modeled after the JACADS facility. Currently the Tooele facility is in testing phase with dummy munitions. Systemization is projected to be completed in February of 1995; when live chemical weapons destruction will begin.

The Big Plan

The Army has incinerators slated for construction in Alabama, Arkansas, and Oregon in 1995. They also plan to acquire a permit and to design an incinerator for the Blue Grass Army Depot.

The Army also says that they have no plans for future use of the facilities after the weapons are destroyed. Most Bluegrass residents are skeptical.

“We’re concerned,” says Charles Bracelen, “that our community could become recipients of some of the worst stuff east of the Mississippi. Accidents could happen, and we are concerned abou the long range health effects of living near such an incinerator.”

Twelve county fiscal courts passed resolutions opposing the Army’s plan to incinerate. So did the governments of Berea, Richmond, and Lexington; three consecutive Kentucky governors have also opposed it.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Richmond’s Nerve Gas Nightmare in 1994 – Ace September 1994